Video 2000 was developed jointly by

Philips and Grundig as a replacement for their ageing VCR, VCR-LP and

SVR format machines and as a direct competitor to VHS and BETA. It

boasted a flip-over cassette fractionally bigger than a VHS cassette,

which could record up to 4 hours on each side. It also used a system of

"Automatic" tracking with it's Dynamic Track Following (DTF) system.

This meant that the tracking was always 100% perfect even on still pause

and picture search modes. It achieved this by having the video heads

mounted on piezo electric actuators which followed the tracks as they

were scanned.

During

the course of the 1970's, Philips, in Holland, and their German

associates Grundig continued to develop the VCR format, increasing both

the record/playback time and the quality of the images, and adding more

and more features to their already sophisticated machines. This

development spawned VCR-LP and SVR, but by the end of the seventies

Philips were promising the imminent arrival of a remarkable new format.

This was called VCC, for Video Compact Cassette, but is more usually

known as Video 2000.

(Philips also invented the

standard music cassette format, which they called ACC -- Audio Compact

Cassette. This name didn't catch on either!)

Despite missing

several launch dates, when V2000 finally arrived in 1980 it was indeed

as revolutionary as they had promised. Alone of all video cassette

formats, VCC tapes could be turned over, just like audio tapes. This

meant that a cassette almost exactly the same size as a VHS tape could

hold six or even eight hours, in total. A later version with long play

increased this to a staggering 16 hours!

V2000

machines were also extremely sophisticated, using microprocessor control

for all manner of trick-play and programming features. Perhaps the most

advanced feature of all was Dynamic Track Following, or DTF; this was

an automatic tracking system which moved the heads as they scanned each

track:

The head chips were mounted on the drum on tiny chips of

piezo-electric crystal. This crystal changes shape when an electric

current is passed through it, so by applying the appropriate signal, the

heads could be kept in the perfect position at all times. Consequently,

V2000 decks needed no Tracking control, and could produce a perfect,

noise-free picture at all speeds, in both directions (even playing in

reverse), and on recordings made on other machines which were out of

alignment.

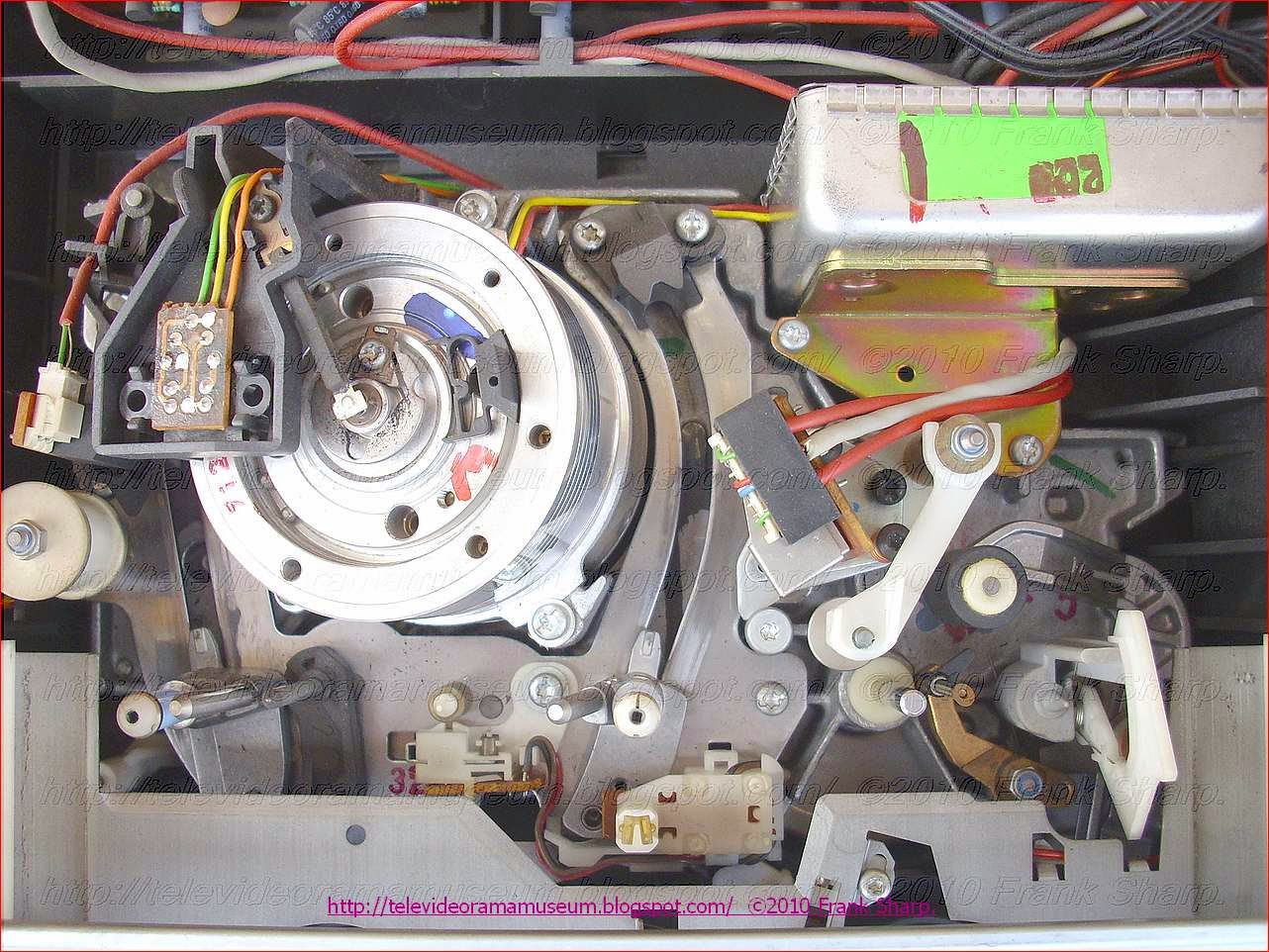

General Construction

On the plus side these VCR's were construted in a modular fashion with

each printed circuit board carrying out a distinct function.

On the down side, these many PCB are connected together using plugs,

sockets and wire links which are prone to failure. The electronics

inside the VCR's is by todays standard fairly straight forward with

many discrete componenets being used together to perform the complex

functions required. This means getting hold of components to repair

electrical problems is by and large still possible. However this good

news is more than wiped out by the fact that it is now near impossible

to get hold of mechanical parts such as pressure rollers, capstan motors

and video heads. For the most part it is a case of having to break up

several machines to get one working.

Video heads for V2000 machines are now rare and extremely difficult to

obtain.

Specifications

|

System

Video recording system

V2000, Rotary two-head helical scanning

Video Signal

CCIR standards, PAL colour

Aerial input

75-ohm, asymmetrical aerial socket

Channel coverage

UHF: Western European

channels band IV/V

471.25-855.25 Mhz

(Up to 99 programmes can be preset.)

RF output signal

UHF channels E30 to E43 (variable)

75 ohms, unbalanced

Video

Horizontal resolution

Luminance 3MHz ( -20db)

Chroma 600khz (-26db)

B/W:312 lines

Video S/N

Better than 44dB CCIR

421-2 annex III

Drop-Out compensation

> 16db, 5 lines max

Audio frequency response

50Hz to 10,000Hz ( 8db )

Audio S/N

Approx 50dB DIN 45500

Inputs and outputs

Video input

VIDEO IN: Via A-V adaptor

1.0 V (p-p)

75 ohms, unbalanced,

sync negative

Video output

VIDEO OUT: Via A-V adaptor

1.0 V (p-p)

75Ohms, unbalanced,

sync negative

Audio inputs

AUDIO IN: Via A-V adaptor

|

- Audio outputs

- AUDIO OUT: Via A-V adaptor

- Tuner input sensitivity

- < 120 µ V Band IV > V

Tape transport

- Tape speed 24.40 mm/sec.

- Maximum recording time

- 2 x 4 hours 0 min. (with VCC-480 cassette)

- Fast forward/rewind time

- 180 sec. (with VCC-480)

Timer

- Clock

- LED

- Time indication

- 24-hour cycle

- Timer setting Only for recording

- Power backup

- incorporating self charging circuit

General

- Power requirements

- 240v AC, 50-60 Hz

- Power consumption

- 75W ( 15W standby )

- Dimensions

- Approx. 540 x 365 x 365 mm (w/h/d)

- including projecting parts and controls

- Weight

- Approx. 17.5 kg net

|

Video 2000 was developed jointly by

Philips and Grundig as a replacement for their ageing VCR, VCR-LP and

SVR format machines and as a direct competitor to VHS and BETA. It

boasted a flip-over cassette fractionally bigger than a VHS cassette,

which could record up to 4 hours on each side. It also used a system of

"Automatic" tracking with it's Dynamic Track Following (DTF) system.

This meant that the tracking was always 100% perfect even on still pause

and picture search modes. It achieved this by having the video heads

mounted on piezo electric actuators which followed the tracks as they

were scanned.

The first Video 2000 format machine from

Philips was the VR2020 of 1980. This was a pretty basic machine even by

1980 standards, but it sold in reasonable numbers. The first Grundig

V2000 machine was the model 700 "2x4", which was launched at pretty much

the same time*. The Grundig machine was slightly smaller and lighter

than the Philips, but had a virtually identical basic set of features.

Superficially the first generation

Philips Video 2000 machines resembled their earlier relatives, the VCR

and VCR-LP machines (N1500, N1700 etc.) They were roughly the same size

and weight as their older relatives and had the same "slopey front"

styling, however, inside they were far more advanced.

The new machines

were operated with all-electronic soft-touch buttons, and a

microprocessor was used to control the tape transport, the clock, the

counter and the timer. All the machines featured a "Goto" button whereby

a specific tape-counter number could dialled in and the machine would

speed off and find it. There was a problem with this because the tape

had to have been initially rewound to the beginning if the counter was

to be relied on to find a specific program. If the counter had gone

backwards beyond zero or had gone past 9999, then the machine would wind

the tape the wrong way to get to the specific number.

Although none of

the VR2020, VR2021 or VR2022 had a remote control facility as standard,

they could all be converted to remote control with a box that plugged

into the back of the machine and a little infra-red receiver which

clipped into the front.

Of the Philips VR2020 there were several

badge engineered versions from manufacturers such as ITT, Pye etc. Bang

and Olufsen made a version of the VR2020 called the 8800, but this

looked significantly different from the Philips original. It had a

remote control receiver built in as standard, but, strangely, it also

had a modified audio response to suit B&O's then current range of

televisions.etc.

Soon after the VR2020 came the Philips

VR2021 and VR2022. Although the VR2021 had an identical feature set to

the VR2020, it had more in common electronically with the VR2022 which

had extra "Trick-play" facilities such as noise-free picture search and

still pause.

These two newer machines also used much nicer looking

chrome on the front panel instead of aluminium which tended to corrode

easily.

There was briefly a stereo version of the VR2022 called the

VR2022S but this was only available in certain European countries and

not in the UK.

Next came the VR2023 and VR2024. These

machines resembled the 3 Philips Video 2000 machines before them,

although some of the timer controls were now covered by a little flap

and the search and still pause (and an extra slow-motion button) were on

separate buttons below the standard controls.

These two new machines

also featured a remote control interface as standard. The difference

between the VR2023 and the VR2024 was that the latter model was a linear

stereo version of the VR2023, making it the first

(universally-available) stereo Video 2000 machine. Philips soon

discovered a problem with the front panels of these two machines: the

microprocessor that controlled the buttons would sometimes lock-up if

two buttons were pressed in quick succession which meant that if the

problem occurred, the machine had to be unplugged from the mains for a

few seconds before any further commands could be given.

The next Philips Video 2000 machine to

appear was the VR2025 and this was to be Philips' first front loading

Video 2000 machine. However, it was merely a Grundig "2x4 Stereo" with a

slightly different colour scheme and a Philips badge. No real attempt

was made to disguise this machine; it even had the classic Grundig

unfathomable timer, and peculiar tape transport legends such as "Tape"

which meant "Stop" and "Cassette" which meant "Eject".

Later came a second generation of Philips

Video 2000 machines including a battery operated portable model. These

were all much smaller than their first generation relatives and

culminated in Philips' top models, the VR2350 "Matchline" and the VR2840

which featured linear stereo audio and a long-play mode (XL or

eXtra-Long) to provide a staggering 16 hours from a single tape, before

the format was discontinued in 1985.

As a point of interest, Grundig made a

very cheap Video 2000 machine (model 1600) which didn't have Dynamic

Track Following at all, instead it used an "automatic tracking" system

like many VHS machines of the day. This was okay to replay tapes

recorded on itself but was famously awful when it came to replaying

tapes recorded on another machine.

PAL and NTSC VHS video tapes Tape speed:

PAL

SP: 23,39 mm/sec

LP: 11,7 mm/sec

NTSC

SP: 33.35 mm/sec (1 3/8 inches/s)

LP: 16.67 mm/sec (11/16 inches/s)

EP: 11.11 mm/sec (7/16 inches/s)

Tape formats

| PAL/SECAM times | NTSC times

name length/metres | SP LP | SP LP EP

============================================================================

E-30 45 m 30 min 60 min 22 min 44 min 66 min

E-60 88 m 60 min 120 min 44 min 88 min 132 min

E-90 130 m 90 min 180 min 65 min 130 min 195 min

E-120 173 m 120 min 240 min 86 min 172 min 258 min

E-180 258 m 180 min 360 min 129 min 258 min 387 min

E-240 346 m 240 min 480 min 173 min 346 min 519 min

E-300 432 m 300 min 600 min 216 min 432 min 648 min

T-20 44 m 28 min 56 min 20 min 40 min 60 min

T-30 64 m 42 min 84 min 30 min 60 min 90 min

T-45 94 m 63 min 126 min 45 min 90 min 135 min

T-60 125 m 84 min 168 min 60 min 120 min 180 min

T-90 185 m 126 min 252 min 90 min 180 min 270 min

T-120 246 m 169 min 338 min 120 min 240 min 360 min

T-160 326 m 225 min 450 min 160 min 320 min 480 min

T-200 407 m 281 min 562 min 200 min 400 min 600 min

Grundig AG

is (WAS) a German manufacturer of consumer electronics for

home entertainment which transferred to Turkish control in the

period 2004-2007. Established in 1945 in Nuremberg, Germany

by Max Grundig the company changed hands several times before

becoming part of the Turkish Koç Holding group. In 2007, after

buying control of the Grundig brand, Koc renamed its

Beko Elektronik white goods

and consumer electronics division Grundig Elektronik A.Ş., which has

decided to merge with Arçelik A.Ş. as declared on February 27, 2009

Max Grundig

Max Grundig (7

May 1908 – 8 December 1989) was the founder of electronics company

Grundig AG.Max Grundig is one of the leading business personalities of

West German post-war society, one of the men responsible for the German

“Wirtschaftswunder” (post-war economic boom).

GRUNDIG Early years

Max

Grundig was born in Nuremberg on May 7, 1908. His father died early, so

Max and his three sisters grew up in a home without a father. At 16,

Max Grundig began to be fascinated by radio technology, which at the

time was gaining in popularity. He built his first detector in the

family’s apartment, which he had turned into his own laboratory. In

1930, he turned his hobby into his profession and opened a shop for

radio sets in Fürth with an associate. The business prospered and soon

Grundig was able to employ his sisters and buy out his associate. By

1938, he was already manufacturing 30,000 small transformers.

GRUNDIG Success after World War II

Max

Grundig’s real success story began after World War II. On May 15, 1945,

Grundig opened a production facility for universal transformers at

Jakobinerstraße 24 in Fürth. Using machines and supplies from the war

era, he established the basis for what would turn into a global company

at this address. In addition to transformers, Grundig soon manufactured

tube-testing devices. As manufacturing radios was subject to a licence,

Grundig had the brilliant idea of developing a kit that would allow

anyone to quickly build a radio on their own. This kit was sold as a

“toy” called “Heinzelmann”.

Following

the monetary reform, Max Grundig quickly expanded his production under

the new company name “Grundig Radio-Werke GmbH” and served the expanding

mass market. From 1952, his company was the biggest European

manufacturer of radios and the worldwide leader in the production of

audio tape recorders.

Grundig

became a real pioneer in consumer electronics. From 1951, the company’s

portfolio also included the production and distribution of television

sets, and dictaphones were added in 1954. The company was turned into a

shareholding company, the Grundig AG, in 1971. In the 1970s, the company

was one of the leading companies in Germany, employing more than 38,000

people in 1979. Max Grundig had built a strong company from the ruins

of the war.

GRUNDIG and the rules are changing

In

the second half of the 1970s, another innovation entered the market for

consumer electronics, the VCR. And with the VCR, competitors from Japan

and later other countries of the Far East entered the world market.

Even though the European competitors Philips and Grundig had developed

the superior technology for recording video, the Japanese VHS succeeded

on the market. The rules of the game changed dramatically in the field

of consumer electronics. The competition for establishing the video

standard proved that companies could only succeed in consumer

electronics with the financial power of global corporations. In 1979,

Max Grundig decided to sell some shares to his Dutch competitor Philips,

and in 1984 he began the process of restructuring the ownership of the

Grundig companies, which would be completed two decades later.

Max

Grundig died on December 8, 1989 in Baden-Baden. The Grundig name

continues to be known to this day and is now a globally recognised brand

for innovative consumer electronics. Max Grundig is remembered in

Germany as a dynamic entrepreneur from the post-war era.

He was married lastly to Chantal Grundig.

Early history

The

history of the company began in 1930 with the establishment

of a store named Fuerth, Grundig & Wurzer (RVF), which

sold radios. After World War II Max Grundig recognized the

need for radios in Germany, and in 1947 produced a kit, while a

factory and administration centre were under construction at

Fürth. In 1951 the first televisions were manufactured at the

new facility with the company and the surrounding area growing

rapidly. At the time Grundig was the largest radio

manufacturer in Europe. Divisions in Nuremberg, Frankfurt and

Karlsruhe were set up.

Grundig in Belfast

Grundig in Belfast

A

plant was opened in 1960 to manufacture tape recorders in

Belfast, Northern Ireland, the first production by Grundig

outside Germany. The managing director of the plant Thomas

Niedermayer, was kidnapped and later killed by the Provisional

IRA in December 1973. The factory was closed with the loss of around 1000 jobs in 1980.

Philips takeover

In

1972, Grundig GmbH became Grundig AG. After this Philips

began to gradually accumulate shares in the company over the

course of many years, and assumed complete control in 1993.

Philips resold Grundig to a Bavarian consortium in 1998 due to

unsatisfactory performance.

In

1972, Grundig GmbH became Grundig AG. After this Philips

began to gradually accumulate shares in the company over the

course of many years, and assumed complete control in 1993.

Philips resold Grundig to a Bavarian consortium in 1998 due to

unsatisfactory performance.

Later history

At

the end of June 2000 the company relocated its headquarters

in Fürth and Nuremberg. Grundig lost €1.281 million the

following year. In autumn 2002, Grundig's banks did not extend

the company's lines of credit, leaving the company with an

April 2003 deadline to announce insolvency. Grundig AG

declared bankruptcy in 2003, selling its satellite equipment

division to Thomson. In 2004 Britain's Alba plc and the Turkish Koc's Beko

jointly took over Grundig Home InterMedia System, Grundig's

consumer electronics division. In 2007 Alba sold its half of

the business to Beko for US$50.3 million, although it retained the licence to use the Grundig brand in the UK until 2010, and in Australasia until 2012.

...........................................The Federal Republic of Germany: Holding the Ring?

For more than thirty years after t he Second World War, consumer

he Second World War, consumer

electronics in West Germany, as elsewhere, was a growth industry.

Output growth in the industry was sustained by buoyant consumer

demand for successive generations of new or modified products,

such as radios (which had already begun to be manufactured, of

course, before the Second World War), black-and-white and then

colour television sets, hi-fi equipment.” Among the largest West

European states, West Germany had by far the strongest industry.

Even as recently as 1982, West Germany accounted for 60 per cent

of the consumer electronics production in the four biggest EEC

states. The West German industry developed a strong export

orientation--in the early 1980s as much as 60 per cent of West

German production was exported, and West Germany held a larger

share of the world marltet than any other national industry apart

from the]apanese.ltwas also technologicallyextremelyinnovative-

the first tape recorders, the PAL colour television technology, and

the technology which later permitted the development of the video

cassette recorder all originated in West Germany.

The standard-bearers of the West German consumer electronics

industry were the owner-managed firm, Grundig, and Telefunken,

which belonged to the electrical engineering conglomerate, AEG-

Telefunlten. The technological innovations for which the West

German industry became famous all stemmed from the laboratories

of Telefunlten, which, in the 19605, still constituted one of AEG’s

most profitable divisions. Telefunlcen and Grundig together prob-

ably accounted for around one-third of employment in the German

Industry in the mid-1970s. Both had extensive foreign production

facilities. At the same time, compared with the other EEC states,

there was still a relatively large number of small and medium-sized

consumer electronics firms in Germany. Besides Grundig and

Telefunken, the biggest were Blaupunkt, a subsidiary of Bosch, the

automobile components manufacturer, Siemens, and the sub-

sidiaries of the ITT-owned firm, SEL. Up until the late 1970s, there

was relatively little foreign-owned manufacturing capacity in the

West German consumer electronics industry.

GOVERNMENTS, MARKETS, AND REGULATION

During the 1970s, this picture of a strong West German

During the 1970s, this picture of a strong West German

consumer electronics industry began slowly to change and, by the end of the 19705, colour television manufacture no longer offered a guarantee for the continued prosperity or even survival of the German industry. The market for colour television sets was increasingly saturated——by 1978 56 per cent of all households in

West Germany had a colour television set and 93 per cent of all households possessed a television set of some kind.2° From 1978 onwards, the West German market for colour television sets began

to contract. Moreover, the PAL patents began to expire around

1980 and the West German firms then became exposed to more

intense competition on the (declining) domestic market.

The West German firms’ best chances for maintaining or

expanding output and profitability lay in their transition to the

manufacture of a new generation of consumer electronics products,

that of the video cassette recorder (VCR). Between 1978 and 1983,

the West German market for VCRs expanded more than tenfold, so

that, by the latter year, VCRs accounted for over a fifth of the

overall consumer electronics market.“ However, in this product

segment, Grundig was the only West German firm which, in

conjunction with Philips, managed to establish a foothold, while

the other firms opted to assemble and/or sell VCRs manufactured

according to one or the other of the two Japanese video

technologies. By 1981, the West German VCR market was more

tightly in the grip of Japanese firms than any other segment of the

market. More than any other, this development accounted for the

growing crisis of the West German consumer electronics industry in

the early 1980s. The West German market stagnated, production

declined as foreign firms conquered a growing share of the

domestic market and this trend was not offset by an expansion of

exports, production processes were rationalized to try to cut costs

as prices fell, employment contracted,” and more and more plants

were either shut down or—more frequently——taken over.

The

relationship between the state and the consumer electronics industry in

the long post-war economic ‘boom’ was of the ‘arm’s length’ kind which

corresponded to the West German philosophy

of the ‘social market

economy’. The state's role was confined largely to ‘holding the ring’

for the firms and trying to ensure by means of competition policy that

mergers and take-overs did not enable any single firm or group of firms

to achieve a position of market domination and suspend the ‘free play of

market forces’.

The implementation of competition policy was the

responsibility of the Federal Cartel Office (FCO), which must be

informed of any planned mergers or take-overs if the two firms each have

a turnover

exceeding 1 DM billion or one of them has a turnover of more than

2 DM billion. The FCC must reject any proposed merger which, in

its view, would lead to the emergence of a, or strengthen any

existing, position of market domination.“

Decisions of the FCO may be contested in the Courts, and firms

whose merger or take-over plans have been rejected by the Cartel

Office may appeal for permission to proceed with their plans to the

Office may appeal for permission to proceed with their plans to the

Federal Economics Minister. He is empowered by law to grant such

permission when it is justified by an ‘overriding public interest’ or

‘macroeconomic benefits’, which may relate to competitiveness on

export markets, employment, and defence or energy policy.”

However, the state had no positive strategy for the consumer

electronics industry and industry, for its part, appeared to have no

demands on the state, other than that, through its macroeconomic

policies, it should provide a favourable business environment. This

situation changed only when, as from the late 1970s onwards, the

Japanese export offensive in consumer electronics plunged the West

German industry into an even deeper crisis.

The Politics of European Restructuring

The burgeoning crisis of not only the West German, but also the

other national consumer electronics industries in the EC in the

early 1980s prompted pleas from the firms (and also organized

labour) for protective intervention by the state——by the European

Community as well as by its respective national Member States.

The partial ‘Europeanization’ of consumer electronics politics

reflected the strategies chosen and pursued by the major European

firms to try to counter, or avoid, the Japanese challenge. These

strategies contained two major elements: measures of at least

temporary protection against Japanese imports to give the firms

breathing space to build up or modernize their production

capacities and improve their competitiveness uis-ci-uis the Japanese

and partly also to put pressure on the Japanese to establish

production facilities in Europe and produce under the same

conditions as the European firms and (b), through mergers, take-

overs, and co-operation agreements, to regroup forces with the aim

of achieving similar economies of scale to those enjoyed by the most

powerful Japanese firms. The first element of these strategies

implicated the European Community in so far as it is responsible

for the trade policies of its Member States. The second element did

not necessarily involve the European Community, but had a Euro-

pean dimension to the extent that most of the take-overs and mergers

envisaged in the restructuring of the industry involved firms from

two or more of the EEC Member States, including the French state-

owned Thomson (see above). As this ‘regrouping of the forces’ of

the European consumer electronics industry was to unfold at first

largely on the West German market, the firms could only

implement their strategies once they had obtained the all-clear of

the FCO or, failing that, of the Federal Economics Ministry.

The Politics of Video Recorder Trade between japan and the EEC:

The Dutch-based multinational conglomerate, Philips, was the first

firm in the world to bring a VCR on to the market. Between 1972

and 1975, it had no competitors at all in VCR manufacture and, as

late as 1977, it split up the European market with Grundig, with

which Philips developed the V2000 VCR which came on to the

market in 1980. By this time, the Japanese consumer electronics

firms had already built up massive VCR production capacities and

had cornered first their own market and then, unchallenged by the

European firms, the American as well. With the advantage of much

greater economies of scale, they were able to manufacture and offer

VCRs more cheaply than Philips and Grundig when the VCR

market did eventually ‘take off‘ in Western Europe. German

imports of VCRs, for example, increased almost eightfold between

1978 and 1981.2

The immediate background to the calls for protection against

imported Japanese VCRs by European VCR manufacturing firms

was formed by massive cuts in price s for Japanese VCRs, as a

s for Japanese VCRs, as a

consequence of which, in 1982, the market share held by the V2000

VCR manufactured by Philips and Grundig declined sharply.”

Losses incurred in VCR manufacture led to a dramatic worsening

of Grundig’s financial position. In November 1982 Philips and

Grundig announced that they were considering taking a dumping

case against the Japanese to the European Commission. The case,

which was later withdrawn, can be seen as the first move in a

political campaign designed to secure controls or restraints on

Japanese VCR exports to the EEC states. This campaign was

pursued at the national and European levels, both through the

national and European trade associations for consumer electronics

firms and particularly through direct intervention by the firms at

the national governments and the European Commission. However,

the European firms, many of whom had licensing agreements with

the Japanese, were far from being united behind it.

Philips, seconded by its VCR partner, Grundig, was the ‘real

protagonist’ of protectionist measures against Japanese VCRs. In

pressing their case on EEC member states and the European

Commission, they emphasized the unfair trading practices of the

Japanese in building up production capacities which could meet the

entire world demand for VCRs (‘laser-beaming’), and the threats

which the Japanese export offensive posed to jobs in Western

Europe and to the maintenance of the firms’ R. 8: D. capacity and

technological know-how. Above all, however, was the threat which

the crisis in VCR trade and the consumer electronics industry

generally posed to the survival of a European microelectronic

components industry, over half of whose output, according to

Grundig, was absorbed in consumer electronics products.”

These arguments found by all acco unts a very receptive audience at the European Commission, where, by common consent of German participants in the policy-formation process, Philips wields great political influence. By all accounts, Philips‘s pressure was also responsible for the conversion to the protectionist camp of the Dutch Government, which hitherto had been a bastion of free trade philosophy within the EEC. By imposing unilateral import controls through the channelling of imported VCRs through the customs depot at Poitiers (see above), the French Government had already staked out its position on VCR trade with Japan. It presumably

unts a very receptive audience at the European Commission, where, by common consent of German participants in the policy-formation process, Philips wields great political influence. By all accounts, Philips‘s pressure was also responsible for the conversion to the protectionist camp of the Dutch Government, which hitherto had been a bastion of free trade philosophy within the EEC. By imposing unilateral import controls through the channelling of imported VCRs through the customs depot at Poitiers (see above), the French Government had already staked out its position on VCR trade with Japan. It presumably

required no convincing by Philips and Grundig on the issue,

although it is interesting to speculate over the extent to which its

stance also reflected the preferences of Thomson which in the past

had been the ‘chief of the protectionists’ in the European

industry.”

With the Dutch Government having been shifted into the

protectionist camp by Philips, the greatest resistance to the

imposition of some form of import controls on Japanese VCRs

could have been expected to come from the West German

Government. Along with the Danish and (hitherto) the Dutch

Governments, the West German Government had generally been

the stoutest defender of free trade among the EEC Member States.

The Federal Economics Ministry’s antipathy towards import

controls may in fact have had some impact on the form of

protection ultimately agreed by the EEC Council of Ministers,

which was a ‘voluntary self-restraint agreement’ with japan.

However, even such self-restraint agreements had in the past been

vetoed by West Germany in the Council. The West German

Government’s abstention in the vote on the agreement in the

Council of Ministers signified if not a radical, then none the less a

significant, modification of its past trade policy.

Within the Bonn Economics Ministry, the section for the

electrical engineering industry-—characteristically—had the most

receptive attitude to the V2000 firms’ case. Elsewhere in the

Ministry, in the trade and European policy and policy principles

divisions and at the summit, the Ministry’ s traditional policy in

s traditional policy in

favour of free trade was given up much more reluctantly. The

Ministry did not oppose the voluntary restraint agreement after it

had been negotiated, but it may be questioned whether the

Ministry’s acquiescence in the agreement was motivated solely by its

feeling of impotence vis-£1-vis the united will of the other Member

States. Abstaining on the vote in the Council of Ministers enabled

the V2000 protectionist lobby to reap its benefits without the West

German Government being held responsible for its implementation.

The Govemment’s abstention may equally have been the result of

the pressure exerted on the Economics Ministry by the V2000

firms, particularly Philips and Grundig, both of which engaged in

bilateral talks with the Ministry, and from the consumer electronics

sub-association of the electrical engineering trade association of the

ZVEI (Zentralverband der Elektrotechnischen lndustrie), in which

a majority of the member firms had sided with Philips and Grundig.

The Ministry, by its own admission, did not listen as closely to the

firms which were simply marketing Japanese VCRs as to those

which actually manufactured VCRs in Europe: ‘we were interested

in increasing the local content (of VCRs) to preserve jobs.’

The success of the V2000 firms in obtaining any agreement at all

The success of the V2000 firms in obtaining any agreement at all

from the Japanese to restrain their exports of VCRs to the EEC

does not mean that they were happy with all aspects of the

agreement, least of all with its contents concerning VCR prices and

concrete quotas which were agreed with the Japanese. As the

market subsequently expanded less rapidly than the European

Commission had anticipated, the quota allocated to Japanese

imports (including the ‘kits’ assembled by European licensees of

Japanese firms) amounted to a larger share of the market than

expected and the European VCR manufacturers did not sell as

many VCRs as the agreement provided. Ironically, within a year of

the adoption of the agreement, both Philips and Grundig announced

that they were beginning to manufacture VCRs according to the

Japanese VHS technology and by the time the agreement had

expired (to be superceded by increased tariffs for VCRs) in 1985,

the two firms had stopped manufacturing V2000 VCRs altogether.

The Politics of Transnational European Mergers and Take-overs

The wave of merger and take-over activity in the European

consumer electronics industry which peaked around 1982 and

1983 had begun in West Gemany in the late 1970s, when Thomson

swallowed up several of the smaller West German firms- Normende,

Dual, and Saba ...and Philips, apparently reacting to the threat it

perceived Thomson as posing to its West German interests, bought

a 24.5 per cent shareholding in Grundig.3° The frenzied series of

successful and unsuccessful merger and take-over bids which

unfolded in 1982 and 1983 is inseparable from the growing crisis of

the European industry and the major European firms’ perceptions

as to how they could restructure in order to survive in the face of

Japanese competition.

The first candidate which emerged for take-over on the West

German market was Telefunken, for which AEG, itself in desperate

financial straits, had been seeking a buyer since the late 1970s.

Telefunken’s heavy indebtedness, which was largely a consequence

of losses it had incurred in its foreign operations, posed a

formidable obstacle to its disposal, however, and first Thomson,

which had bought AEG’s tube factory, and then Grundig, baulked

at taking it on as long as AEG had not paid off its debts. While talks

on Telefunken’s possible sale to Grundig were still going on in

1982, Grundig’s own financial position was quickly worsening as a

result primarily of its mounting losses in VCR manufacture.

Grundig c onfessed publicly that if the firm carried on five more

onfessed publicly that if the firm carried on five more

years as it was doing, it would ‘go under like AEG’, which, in

summer 1982, had become insolvent. Grundig intensified his search

for stronger partners, which he had apparently begun by talking

with Siemens in 1981. In late 1982, at the same time as Grundig

and Philips were pressing for curbs on Japanese VCR imports,

Grundig floated the idea of creating, based around Grundig, a

European consumer electronics ‘superfirm’ involving Philips,

Thomson, Bosch, Siemens, SEL, and Telefunken. Most of the

prospective participants in such a venture were unenthusiastic

about Grundig’s plans, however, and the outcome of Grundig’s

search for a partner or partners to secure its survival was that

Thomson offered to buy a 75.5 per cent shareholding in the firm.

Political opinion in West Germany was overwhelmingly, if not

indeed uniformly, hostile to Thomson’s plan to take over Grundig.

The political difficulties which Thomson and Grundig faced in

securing special ministerial permission for the ir deal were exacer-

ir deal were exacer-

bated by the probability of job losses given a rapidly deteriorating

labour market situation, and by the fact that, as late as 1982 and

early 1983, an election campaign was in progress. Moreover, the

Federal Economics Ministry was apparently concerned that, if

Thomson took over Grundig, the West German Government would

have been exposed to the danger of trade policy blackmail from the

French Government, which could then have demanded increased

protection for the European consumer electronics industry as the

price for Thomson not running down employment at Grundig (and

in other West German subsidiaries).

The decisive obstacle to Thomson's taking over Grundig,

however, lay not with the position of the Federal Economics

Ministry (or that of the Government or the FCO or the Deutsche

Bank), but rather in that of Grundig’s minority shareholder,

Philips. Against expectations, the FCO announced that it would

approve the take-over, but only provided that Philips gave up its

shareholding in Grundig and that Grundig also abandoned its plans

to assume control of Telefunken. As talks on Grundig’s plan to take

over Telefunken had already been suspended, the latter condition

posed no problem to Thomson’s taking over Grundig.

Once it had been put on the spot by the FCO's decision, Philips

was forced to leave its cover and declare that it would not withdraw

from Grundig. Apart from its general concern at being confronted

with an equally strong competitor on the European consumer

electronics market, Philips’s motives in thwarting Thomson's take-

over of Grundig were probably twofold. First, Thomson evidently

did not want to commit itself to continue manufacturing VCRs

according to the Philips—-Grundig V2000 technology, but wanted

rather to keep the Japanese (VHS) option open and, according to its

public declarations, to work with Grundig on the development of a

new generation of VCRs. Secondly, Philips was, ahead of Siemens,

Grundig’s biggest components supplier, with annual sales to

Grundig worth several hundred million Deutschmarks. lf Thomson

had taken over Grundig, this trade would have been lost.

A sequel to the failure of Thomson's bid for Grundig was that in

1984, with bank assistance, Philips assumed managerial control of

Grundig. Thus, at the end of this phase of the restructuring

programme of the European consumer electronics industry, two

main groups have emerged, one centred around Philips, the other

around Thomson, and Blaupunkt is the only significant firm in

West Germany left under West German control. But a common

European response (i.e. one involving Philips and Thomson) to the

Japanese challenge of the kind which Max Grundig had envisaged

had envisaged

in 1982 had not come about, and may be less likely given

Thomson’s acquisitions in Britain and the US which make it a much

more powerful competitor to Philips. But the acceleration in

Japanese and also Korean inward investment in Europe in 1986-7,

especially in VCR production where there are now a total of twenty

Far Eastern-owned plants, suggests that the process of restructuring

within Europe is far from complete.

The recent experience of the European consumer electronics

industry points to the critical role of the framework and instruments

of regulation in trying to account for the different responses of the

various national industries and governments to the challenges

posed by growing Japanese competitive strength and technological

leadership. At one extreme is self-regulation by individual firms,

where governments eschew any attempt to determine the responses

which particular firms make to changing market conditions, whilst

adopting policy regimes such as tax and tariff structures and

openness to inward investment which critically affect the conditions

under which self-regulation takes place." At the other extreme is

regulation by government intervention at the level of firm strategy,

where governments seek specific policy outcomes by offering

specific forms of inducement to selected firms and denying them to

others.”

HISTORY OF GRUNDIG IN GERMAN:

1930

gründet der Kaufmann und Radiobastler Max Grundig (1908-1989) den

Radio-Vertrieb Fürth, Grundig & Wurzer (RVF), ein

Radio-Fachgeschäft m it Werkstatt. Bald fabriziert der Betrieb auch

Transformatoren und Spulen, später zudem Prüfgeräte. 1934 zahlt Grundig

den Teilhaber und Freund Karl Wurzer aus. 1938 beträgt der Umsatz mehr

als 1 Mio. RM. Während des Krieges fabriziert Grundig im Dorf Vach mit

etwa 600 Personen, darunter vielen Ukrainerinnen, Kleintrafos,

elektrische Zünder und Steuergeräte für die V-Raketen. Das

Grundig-Vermögen schätzt man am Kriegsende auf 17,5 Mio. RM

it Werkstatt. Bald fabriziert der Betrieb auch

Transformatoren und Spulen, später zudem Prüfgeräte. 1934 zahlt Grundig

den Teilhaber und Freund Karl Wurzer aus. 1938 beträgt der Umsatz mehr

als 1 Mio. RM. Während des Krieges fabriziert Grundig im Dorf Vach mit

etwa 600 Personen, darunter vielen Ukrainerinnen, Kleintrafos,

elektrische Zünder und Steuergeräte für die V-Raketen. Das

Grundig-Vermögen schätzt man am Kriegsende auf 17,5 Mio. RM

Ab

18. Mai 1945 kann Grundig wieder in Fürth produzieren. Er lässt

Transformatoren wickeln, Reparaturen ausführen und stellt kurz darauf

das Röhrenprüfgerät «Tubatest» und das Fehler-Suchgerät «Novatest» her.

Ab 15.1.46 lässt Grundig den externen Ing. Hans Eckstein, den früheren

Konstrukteur bei Lumophon, einen Einkreiser-Baukasten mit späterem

Namen «Heinzelmann» entwickeln. Anfang 1946 beschäftigt Grundig ca. 100

Personen. Ab Oktober 1946 läuft die Produktion des «Heinzelmann» und

die Firma stellt bis Ende 1946 391 Baukästen her. Die vierseitige

Geschichte dazu findet sich in der Zeitschrift «rft» 1991, ab Seite 421.

Grundig hat auch 1947 grossen Erfolg, denn ein Baukasten ist ohne

Bezugsschein erhältlich. Das erste Modell (A) ist ein

Zwei-Röhren-Allstromempfänger mit Wehrmachtsröhren RV12P2000. Die

Produktion findet bald mit 120 Mitarbeitern auf 400 qm statt. Anfang

1947 folgt Modell W [634701]. Der Baukasten erreicht 1948 eine Stückzahl

von 39'256 [DRM].

Am 15.3.47

beginnt Grundig mit dem Bau eines modernen Fabrikgebäudes auf 8000 qm

Fläche. Mitte 1948 kann die Firma den Superhet «Weltklang» anbieten; er

findet ebenfalls guten Absatz. 400 Personen arbeiten auf 3000 qm

Fläche. Im Juli 1948 benennt Grundig seine Firma in Grundig-Radiowerke

GmbH um. Jetzt arbeiten 650 Personen im Betrieb. 1949 kommt als erstes

deutsches Nachkriegs-Koffergerät der «Grundig-Boy» auf den Markt. Die

Firma bringt eine Neukonstruktion des «Heinzelmann» auf den Markt.

Zudem entsteht der Vier-Kreis-Super «Weltklang 268GW». Im Mai 1949

erreicht der Betrieb in der Bizone (eigentlich Trizone!) 20 %

Marktanteil [664905]. Die Bizone ist der Zusammenschluss der amerikan.

und brit. Besatzungszone von 1947 bis 8.4.49, die sich ab dann durch den

Anschluss der frz. Besatzungszone zur Trizone erweitert.

erweitert.

Am

16. Mai 1951 übernimmt Grundig die Lumophon-Werke (ebenfalls in Fürth)

für den Betrag von 1,7 Mio. DM. Im gleichen Jahr entstehen erste

Grundig-Tonbandgeräte. 1952 beginnt die Produktion von Fernsehgeräten.

Das Unternehmen beschäftigt nun 6000 Personen und feiert am 12. Mai 1952

den millionsten Rundfunkempfänger. Die Baureihe von 1952/53 ist

erstmals technisch und formal einheitlich gestaltet, wobei Grundig die

prinzipielle Form bis 1956/57 beibehält. Ausser Typ 810 mit

Flankengleichrichter enthalten alle Geräte einen integrierten FM-Teil

mit Ratiodetektor. 1955 bezeichnet sich Grundig als den grössten

Tonbandgeräte-Hersteller der Welt. 1956 kauft er das

Telefunken-Rundfunkgerätewerk Dachau [639071]. 1959 besteht Grundig aus

sieben Werken, zwei Tochtergesellschaften plus einer Neugründung in den

USA. 1964 übernimmt Grundig die Tonfunk-Werke, Karlsruhe. 1969

beteiligt sich Grundig mehrheitlich an der Kaiser-Radio in Kenzingen.

Max Grundig ist seit 1970 gesundheitlich angeschlagen.

1978

gehören 31 Werke, 9 Niederlassungen mit 20 Filialen und drei

Werksvertretungen, 8 Vertriebs- und 200 Exportvertretungen zur Grundig

AG. 1979 beschäftigt das Unternehmen 38'000 Personen; der Umsatz liegt

bei 3 Mrd. DM. Ein Hauptstandort ist Nürnberg. Grundig muss sich jedoch

einer Umstrukturierung unterziehen und Philips erhält 1979 eine

Beteiligung von rund 25 %. 1980/81 muss Grundig einen Verlust von 187

Mio. DM hinnehmen. Zusätzlich scheitert das Gerät «VIDEO 2000»

finanziell.

Eine detaillierte Firmengeschichte enthält das 1983 erschienene Buch: «Sieben Tage im Leben des Max Grundig» von Egon Fein.

1978

gehören 31 Werke, 9 Niederlassungen mit 20 Filialen und drei

Werksvertretungen, 8 Vertriebs- und 200 Exportvertretungen zur Grundig

AG. 1979 beschäftigt das Unternehmen 38'000 Personen; der Umsatz liegt

bei 3 Mrd. DM. Ein Hauptstandort ist Nürnberg. Grundig muss sich jedoch

einer Umstrukturierung unterziehen und Philips erhält 1979 eine

Beteiligung von rund 25 %. 1980/81 muss Grundig einen Verlust von 187

Mio. DM hinnehmen. Zusätzlich scheitert das Gerät «VIDEO 2000»

finanziell.

Eine detaillierte Firmengeschichte enthält das 1983 erschienene Buch: «Sieben Tage im Leben des Max Grundig» von Egon Fein.

Allerdings lässt sich aus [481, Saba] auch wenig Schmeichelhaftes über das Machtstreben von Max Grundig erfahren.

1984

erhöht Philips die Beteiligung um 7 % und übernimmt die

unternehmerische Verantwortung. 1986/87 kann das Unternehmen mit noch

19'500 Mitarbeitern wieder schwarze Zahlen schreiben. 1987/88

beschäftigt Grundig noch 18'700 Personen bei einem Umsatz von

3,2

Mrd. DM, wovon 90 % auf die Unterhaltungselektronik entfallen. In

diesem Geschäftsjahr verlassen 2 Mio. Farbfernsehgeräte und 750'000

Videorecorder die Bänder. Max Grundig stirbt im Dezember 1989 [639071] -

letztlich hatte er nicht das vierblättrige, sondern das dreiblättrige

Kleeblatt als Firmenemblem gewählt.

3,2

Mrd. DM, wovon 90 % auf die Unterhaltungselektronik entfallen. In

diesem Geschäftsjahr verlassen 2 Mio. Farbfernsehgeräte und 750'000

Videorecorder die Bänder. Max Grundig stirbt im Dezember 1989 [639071] -

letztlich hatte er nicht das vierblättrige, sondern das dreiblättrige

Kleeblatt als Firmenemblem gewählt.

Philips hat das

Unternehmen vollständig übernommen. Mitte 90er Jahre beschäftigt

Grundig noch 8000 Personen. Eine detaillierte Firmengeschichte findet

sich in «kleeblatt radio» ab 5/93 des Förderverein des Rundfunkmuseums

der Stadt Fürth eV.

1998 verkaufte Philips das

Unternehmen an ein Konsortium unter Führung von Anton Kathrein von den

Kathrein-Werken. Im Jahre 2001 wurde bei einem Umsatz von 1,2

Milliarden Euro ein Verlust von 150 Millionen Euro erwirtschaftet.

Daher verlängerten die Banken im Herbst 2002 die Kreditlinien nicht

mehr, was zur Insolvenz im April 2003 führte. In der Folgezeit wurden

gewinnbringende Sparten (wie z.B. Bürogeräte, Autoradios) aus dem

Konzern herausgelöst und einzeln verkauft. Verlustreiche Sparten wurden

stillgelegt und die Mitarbeiter entlassen. Heute erhältliche Neuware

von Grundig ist kaum noch "made in Germany".