How many times when watching somewhat at the Tv you said: "Please REPLAY that Scene...." You couldn't until you have had a machine called VideoRecorder........The TeleVideoRamaMuseum shows the Hi Tech behind Old Video Tape Recorders of all types VHS V2000 Beta VCR to show, one more time, what real technology engineering was instead of todays DRM gizmos Crap. Site under development, coming soon !

There are lots of vintage electrical and electronic items that have not survived well or even completely disappeared and forgotten.

Or are not being collected nowadays in proportion to their significance or prevalence in their heyday, this is bad and the main part of the death land. The heavy, ugly sarcophagus; models with few endearing qualities, devices that have some over-riding disadvantage to ownership such as heavy weight,toxicity or inflated value when dismantled, tend to be under-represented by all but the most comprehensive collections and museums. They get relegated to the bottom of the wants list, derided as 'more trouble than they are worth', or just forgotten entirely. As a result, I started to notice gaps in the current representation of the history of electronic and electrical technology to the interested member of the public.

Following this idea around a bit, convinced me that a collection of the peculiar alone could not hope to survive on its own merits, but a museum that gave equal display space to the popular and the unpopular, would bring things to the attention of the average person that he has previously passed by or been shielded from. It's a matter of culture. From this, the Tele Video Rama Web Museum concept developed and all my other things too. It's an open platform for all electrical Electronic TV technology to have its few, but NOT last, moments of fame in a working, hand-on environment. We'll never own Colossus or Faraday's first transformer, but I can show things that you can't see at the Science Museum, and let you play with things that the Smithsonian can't allow people to touch, because my remit is different.

There was a society once that was the polar opposite of our disposable, junk society. A whole nation was built on the idea of placing quality before quantity in all things. The goal was not “more and newer,” but “better and higher" .This attitude was reflected not only in the manufacturing of material goods, but also in the realms of art and architecture, as well as in the social fabric of everyday life. The goal was for each new cohort of children to stand on a higher level than the preceding cohort: they were to be healthier, stronger, more intelligent, and more vibrant in every way.

The society that prioritized human, social and material quality is a Winner. Truly, it is the high point of all Western civilization. Consequently, its defeat meant the defeat of civilization itself.

Today, the West is headed for the abyss. For the ultimate fate of our disposable society is for that society itself to be disposed of. And this will happen sooner, rather than later.

OLD, but ORIGINAL, Well made, Funny, Not remotely controlled............. and not Made in CHINA.

N.V. Philips, the Holland -based electronics giant, has introduced. a completely new home videocassette recording system for the European market and says it will have a U.S. (NTSC color standard) version in about a year. The Video 2000 system was designed for flexibility in adapting to new developments, such as metal tape, stereo sound and special control signals. The cassette, about the same size as a VHS type, contains half-inch tape and can record for up to eight hours on two quarter - inch helically scanned tracks. Like Philips' audio cassette, it is turned over after one track is recorded or played. Future recorder models obviously will have an auto -reverse fea- ture to eliminate the turn -over operation. Perhaps the most noteworthy development in the new system is the inclusion of a Dynamic Track Following circuit that uses auxiliary signals to assure that the head is properly positioned on the tape both for recording and playback for complete compatibility, and to provide clean, noiseless slow -, fast- and stop- motion. The cassette has special indexing tabs to adjust the recorder for either chrome or metal tape (the latter was not available.). The tape has two auxiliary signal tracks (not used in the first machines). Philips' first VCR designed for the new system has a micro -processor wireless remote -control system that not only governs the record and play functions, but tunes in broadcast channels, can locate any segment of the tape by dialing up a four -digit figure corresponding to a number on the digital tape counter, and is used to pre-select any five programs over a 16-day period for automatic recording. The system was co developed with Grundig, which is producing its own VCR models. it's incompatible with all other home VCR systems in use, including Philips' previous system. Magnavox, Philips subsidiary in the United States, currently sells VHS video recorders built by Matsushita of Japan. It's not yet clear whether Magnavox will offer a version of the Philips' system in this country. One possibility offered by the Video 2000 system is a compact portable VCR using one -quarter-inch tape -in effect, a single track instead of two parallel tracks. A Philips spokesman conceded that "in the system it is possible" to do this. Although such a shaved -down cassette wouldn't be compatible in size with the home recorder, conceivably an adapter could be made available to let the big machine scan the mini-cassettes.

Max Grundig (7

May 1908 – 8 December 1989) was the founder of electronics company

Grundig AG.Max Grundig is one of the leading business personalities of

West German post-war society, one of the men responsible for the German

“Wirtschaftswunder” (post-war economic boom).

Max Grundig (7

May 1908 – 8 December 1989) was the founder of electronics company

Grundig AG.Max Grundig is one of the leading business personalities of

West German post-war society, one of the men responsible for the German

“Wirtschaftswunder” (post-war economic boom).

Grundig in Belfast

Grundig in Belfast In

1972, Grundig GmbH became Grundig AG. After this Philips

began to gradually accumulate shares in the company over the

course of many years, and assumed complete control in 1993.

Philips resold Grundig to a Bavarian consortium in 1998 due to

unsatisfactory performance.

In

1972, Grundig GmbH became Grundig AG. After this Philips

began to gradually accumulate shares in the company over the

course of many years, and assumed complete control in 1993.

Philips resold Grundig to a Bavarian consortium in 1998 due to

unsatisfactory performance.For more than thirty years after the Second World War, consumer

electronics in West Germany, as elsewhere, was a growth industry.

Output growth in the industry was sustained by buoyant consumer

demand for successive generations of new or modified products,

such as radios (which had already begun to be manufactured, of

course, before the Second World War), black-and-white and then

colour television sets, hi-fi equipment.” Among the largest West

European states, West Germany had by far the strongest industry.

Even as recently as 1982, West Germany accounted for 60 per cent

of the consumer electronics production in the four biggest EEC

states. The West German industry developed a strong export

orientation--in the early 1980s as much as 60 per cent of West

German production was exported, and West Germany held a larger

share of the world marltet than any other national industry apart

from the]apanese.ltwas also technologicallyextremelyinnovative-

the first tape recorders, the PAL colour television technology, and

the technology which later permitted the development of the video

cassette recorder all originated in West Germany.

GOVERNMENTS, MARKETS, AND REGULATION

During the 1970s, this picture of a strong West German

consumer electronics industry began slowly to change and, by the end of the 19705, colour television manufacture no longer offered a guarantee for the continued prosperity or even survival of the German industry. The market for colour television sets was increasingly saturated——by 1978 56 per cent of all households in

West Germany had a colour television set and 93 per cent of all households possessed a television set of some kind.2° From 1978 onwards, the West German market for colour television sets began

to contract. Moreover, the PAL patents began to expire around

1980 and the West German firms then became exposed to more

intense competition on the (declining) domestic market.

The West German firms’ best chances for maintaining or

expanding output and profitability lay in their transition to the

manufacture of a new generation of consumer electronics products,

that of the video cassette recorder (VCR). Between 1978 and 1983,

the West German market for VCRs expanded more than tenfold, so

that, by the latter year, VCRs accounted for over a fifth of the

overall consumer electronics market.“ However, in this product

segment, Grundig was the only West German firm which, in

conjunction with Philips, managed to establish a foothold, while

the other firms opted to assemble and/or sell VCRs manufactured

according to one or the other of the two Japanese video

technologies. By 1981, the West German VCR market was more

tightly in the grip of Japanese firms than any other segment of the

market. More than any other, this development accounted for the

growing crisis of the West German consumer electronics industry in

the early 1980s. The West German market stagnated, production

declined as foreign firms conquered a growing share of the

domestic market and this trend was not offset by an expansion of

exports, production processes were rationalized to try to cut costs

as prices fell, employment contracted,” and more and more plants

were either shut down or—more frequently——taken over.

Decisions of the FCO may be contested in the Courts, and firms

whose merger or take-over plans have been rejected by the Cartel

Office may appeal for permission to proceed with their plans to the

Federal Economics Minister. He is empowered by law to grant such

permission when it is justified by an ‘overriding public interest’ or

‘macroeconomic benefits’, which may relate to competitiveness on

export markets, employment, and defence or energy policy.”

However, the state had no positive strategy for the consumer

electronics industry and industry, for its part, appeared to have no

demands on the state, other than that, through its macroeconomic

policies, it should provide a favourable business environment. This

situation changed only when, as from the late 1970s onwards, the

Japanese export offensive in consumer electronics plunged the West

German industry into an even deeper crisis.

The Politics of European Restructuring

The burgeoning crisis of not only the West German, but also the

other national consumer electronics industries in the EC in the

early 1980s prompted pleas from the firms (and also organized

labour) for protective intervention by the state——by the European

Community as well as by its respective national Member States.

The partial ‘Europeanization’ of consumer electronics politics

reflected the strategies chosen and pursued by the major European

firms to try to counter, or avoid, the Japanese challenge. These

strategies contained two major elements: measures of at least

temporary protection against Japanese imports to give the firms

breathing space to build up or modernize their production

capacities and improve their competitiveness uis-ci-uis the Japanese

and partly also to put pressure on the Japanese to establish

production facilities in Europe and produce under the same

conditions as the European firms and (b), through mergers, take-

overs, and co-operation agreements, to regroup forces with the aim

of achieving similar economies of scale to those enjoyed by the most

powerful Japanese firms. The first element of these strategies

implicated the European Community in so far as it is responsible

for the trade policies of its Member States. The second element did

not necessarily involve the European Community, but had a Euro-

pean dimension to the extent that most of the take-overs and mergers

envisaged in the restructuring of the industry involved firms from

two or more of the EEC Member States, including the French state-

owned Thomson (see above). As this ‘regrouping of the forces’ of

the European consumer electronics industry was to unfold at first

largely on the West German market, the firms could only

implement their strategies once they had obtained the all-clear of

the FCO or, failing that, of the Federal Economics Ministry.

The immediate background to the calls for protection against

imported Japanese VCRs by European VCR manufacturing firms

was formed by massive cuts in prices for Japanese VCRs, as a

consequence of which, in 1982, the market share held by the V2000

VCR manufactured by Philips and Grundig declined sharply.”

Losses incurred in VCR manufacture led to a dramatic worsening

of Grundig’s financial position. In November 1982 Philips and

Grundig announced that they were considering taking a dumping

case against the Japanese to the European Commission. The case,

which was later withdrawn, can be seen as the first move in a

political campaign designed to secure controls or restraints on

Japanese VCR exports to the EEC states. This campaign was

pursued at the national and European levels, both through the

national and European trade associations for consumer electronics

firms and particularly through direct intervention by the firms at

the national governments and the European Commission. However,

the European firms, many of whom had licensing agreements with

the Japanese, were far from being united behind it.

Philips, seconded by its VCR partner, Grundig, was the ‘real

protagonist’ of protectionist measures against Japanese VCRs. In

pressing their case on EEC member states and the European

Commission, they emphasized the unfair trading practices of the

Japanese in building up production capacities which could meet the

entire world demand for VCRs (‘laser-beaming’), and the threats

which the Japanese export offensive posed to jobs in Western

Europe and to the maintenance of the firms’ R. 8: D. capacity and

technological know-how. Above all, however, was the threat which

the crisis in VCR trade and the consumer electronics industry

generally posed to the survival of a European microelectronic

components industry, over half of whose output, according to

Grundig, was absorbed in consumer electronics products.”

These arguments found by all accounts a very receptive audience at the European Commission, where, by common consent of German participants in the policy-formation process, Philips wields great political influence. By all accounts, Philips‘s pressure was also responsible for the conversion to the protectionist camp of the Dutch Government, which hitherto had been a bastion of free trade philosophy within the EEC. By imposing unilateral import controls through the channelling of imported VCRs through the customs depot at Poitiers (see above), the French Government had already staked out its position on VCR trade with Japan. It presumably

required no convincing by Philips and Grundig on the issue,

although it is interesting to speculate over the extent to which its

stance also reflected the preferences of Thomson which in the past

had been the ‘chief of the protectionists’ in the European

industry.”

Within the Bonn Economics Ministry, the section for the

electrical engineering industry-—characteristically—had the most

receptive attitude to the V2000 firms’ case. Elsewhere in the

Ministry, in the trade and European policy and policy principles

divisions and at the summit, the Ministry’s traditional policy in

favour of free trade was given up much more reluctantly. The

Ministry did not oppose the voluntary restraint agreement after it

had been negotiated, but it may be questioned whether the

Ministry’s acquiescence in the agreement was motivated solely by its

feeling of impotence vis-£1-vis the united will of the other Member

States. Abstaining on the vote in the Council of Ministers enabled

the V2000 protectionist lobby to reap its benefits without the West

German Government being held responsible for its implementation.

The Govemment’s abstention may equally have been the result of

the pressure exerted on the Economics Ministry by the V2000

firms, particularly Philips and Grundig, both of which engaged in

bilateral talks with the Ministry, and from the consumer electronics

sub-association of the electrical engineering trade association of the

ZVEI (Zentralverband der Elektrotechnischen lndustrie), in which

a majority of the member firms had sided with Philips and Grundig.

The Ministry, by its own admission, did not listen as closely to the

firms which were simply marketing Japanese VCRs as to those

which actually manufactured VCRs in Europe: ‘we were interested

in increasing the local content (of VCRs) to preserve jobs.’

The success of the V2000 firms in obtaining any agreement at all

from the Japanese to restrain their exports of VCRs to the EEC

does not mean that they were happy with all aspects of the

agreement, least of all with its contents concerning VCR prices and

concrete quotas which were agreed with the Japanese. As the

market subsequently expanded less rapidly than the European

Commission had anticipated, the quota allocated to Japanese

imports (including the ‘kits’ assembled by European licensees of

Japanese firms) amounted to a larger share of the market than

expected and the European VCR manufacturers did not sell as

many VCRs as the agreement provided. Ironically, within a year of

the adoption of the agreement, both Philips and Grundig announced

that they were beginning to manufacture VCRs according to the

Japanese VHS technology and by the time the agreement had

expired (to be superceded by increased tariffs for VCRs) in 1985,

the two firms had stopped manufacturing V2000 VCRs altogether.

The Politics of Transnational European Mergers and Take-overs

The wave of merger and take-over activity in the European

consumer electronics industry which peaked around 1982 and

1983 had begun in West Gemany in the late 1970s, when Thomson

swallowed up several of the smaller West German firms- Normende,

Dual, and Saba ...and Philips, apparently reacting to the threat it

perceived Thomson as posing to its West German interests, bought

a 24.5 per cent shareholding in Grundig.3° The frenzied series of

successful and unsuccessful merger and take-over bids which

unfolded in 1982 and 1983 is inseparable from the growing crisis of

the European industry and the major European firms’ perceptions

as to how they could restructure in order to survive in the face of

Japanese competition.

Grundig confessed publicly that if the firm carried on five more

years as it was doing, it would ‘go under like AEG’, which, in

summer 1982, had become insolvent. Grundig intensified his search

for stronger partners, which he had apparently begun by talking

with Siemens in 1981. In late 1982, at the same time as Grundig

and Philips were pressing for curbs on Japanese VCR imports,

Grundig floated the idea of creating, based around Grundig, a

European consumer electronics ‘superfirm’ involving Philips,

Thomson, Bosch, Siemens, SEL, and Telefunken. Most of the

prospective participants in such a venture were unenthusiastic

about Grundig’s plans, however, and the outcome of Grundig’s

search for a partner or partners to secure its survival was that

Thomson offered to buy a 75.5 per cent shareholding in the firm.

Political opinion in West Germany was overwhelmingly, if not

indeed uniformly, hostile to Thomson’s plan to take over Grundig.

The political difficulties which Thomson and Grundig faced in

securing special ministerial permission for their deal were exacer-

bated by the probability of job losses given a rapidly deteriorating

labour market situation, and by the fact that, as late as 1982 and

early 1983, an election campaign was in progress. Moreover, the

Federal Economics Ministry was apparently concerned that, if

Thomson took over Grundig, the West German Government would

have been exposed to the danger of trade policy blackmail from the

French Government, which could then have demanded increased

protection for the European consumer electronics industry as the

price for Thomson not running down employment at Grundig (and

in other West German subsidiaries).

The decisive obstacle to Thomson's taking over Grundig,

however, lay not with the position of the Federal Economics

Ministry (or that of the Government or the FCO or the Deutsche

Bank), but rather in that of Grundig’s minority shareholder,

Philips. Against expectations, the FCO announced that it would

approve the take-over, but only provided that Philips gave up its

shareholding in Grundig and that Grundig also abandoned its plans

to assume control of Telefunken. As talks on Grundig’s plan to take

over Telefunken had already been suspended, the latter condition

posed no problem to Thomson’s taking over Grundig.

Once it had been put on the spot by the FCO's decision, Philips

was forced to leave its cover and declare that it would not withdraw

from Grundig. Apart from its general concern at being confronted

with an equally strong competitor on the European consumer

electronics market, Philips’s motives in thwarting Thomson's take-

over of Grundig were probably twofold. First, Thomson evidently

did not want to commit itself to continue manufacturing VCRs

according to the Philips—-Grundig V2000 technology, but wanted

rather to keep the Japanese (VHS) option open and, according to its

public declarations, to work with Grundig on the development of a

new generation of VCRs. Secondly, Philips was, ahead of Siemens,

Grundig’s biggest components supplier, with annual sales to

Grundig worth several hundred million Deutschmarks. lf Thomson

had taken over Grundig, this trade would have been lost.

had envisaged

had envisagedThe recent experience of the European consumer electronics

industry points to the critical role of the framework and instruments

of regulation in trying to account for the different responses of the

various national industries and governments to the challenges

posed by growing Japanese competitive strength and technological

leadership. At one extreme is self-regulation by individual firms,

where governments eschew any attempt to determine the responses

which particular firms make to changing market conditions, whilst

adopting policy regimes such as tax and tariff structures and

openness to inward investment which critically affect the conditions

under which self-regulation takes place." At the other extreme is

regulation by government intervention at the level of firm strategy,

where governments seek specific policy outcomes by offering

specific forms of inducement to selected firms and denying them to

others.”

it Werkstatt. Bald fabriziert der Betrieb auch

Transformatoren und Spulen, später zudem Prüfgeräte. 1934 zahlt Grundig

den Teilhaber und Freund Karl Wurzer aus. 1938 beträgt der Umsatz mehr

als 1 Mio. RM. Während des Krieges fabriziert Grundig im Dorf Vach mit

etwa 600 Personen, darunter vielen Ukrainerinnen, Kleintrafos,

elektrische Zünder und Steuergeräte für die V-Raketen. Das

Grundig-Vermögen schätzt man am Kriegsende auf 17,5 Mio. RM

it Werkstatt. Bald fabriziert der Betrieb auch

Transformatoren und Spulen, später zudem Prüfgeräte. 1934 zahlt Grundig

den Teilhaber und Freund Karl Wurzer aus. 1938 beträgt der Umsatz mehr

als 1 Mio. RM. Während des Krieges fabriziert Grundig im Dorf Vach mit

etwa 600 Personen, darunter vielen Ukrainerinnen, Kleintrafos,

elektrische Zünder und Steuergeräte für die V-Raketen. Das

Grundig-Vermögen schätzt man am Kriegsende auf 17,5 Mio. RM  erweitert.

erweitert. 1978

gehören 31 Werke, 9 Niederlassungen mit 20 Filialen und drei

Werksvertretungen, 8 Vertriebs- und 200 Exportvertretungen zur Grundig

AG. 1979 beschäftigt das Unternehmen 38'000 Personen; der Umsatz liegt

bei 3 Mrd. DM. Ein Hauptstandort ist Nürnberg. Grundig muss sich jedoch

einer Umstrukturierung unterziehen und Philips erhält 1979 eine

Beteiligung von rund 25 %. 1980/81 muss Grundig einen Verlust von 187

Mio. DM hinnehmen. Zusätzlich scheitert das Gerät «VIDEO 2000»

finanziell.

1978

gehören 31 Werke, 9 Niederlassungen mit 20 Filialen und drei

Werksvertretungen, 8 Vertriebs- und 200 Exportvertretungen zur Grundig

AG. 1979 beschäftigt das Unternehmen 38'000 Personen; der Umsatz liegt

bei 3 Mrd. DM. Ein Hauptstandort ist Nürnberg. Grundig muss sich jedoch

einer Umstrukturierung unterziehen und Philips erhält 1979 eine

Beteiligung von rund 25 %. 1980/81 muss Grundig einen Verlust von 187

Mio. DM hinnehmen. Zusätzlich scheitert das Gerät «VIDEO 2000»

finanziell.

d of recording and reproduction of wide frequency band video

signals onto or from a magnetizable recording carrier, carried out by

the following means: means for separating of the video frequency signals

into first and second signals of lower and upper frequency range

respectively, for converting said second signal into a third signal the

frequency range of which equaling that of said first signal, for

frequency modulating a carrier wave frequency by said first and third

signals and for recording the frequency modulated signals by means of a

twin head, for reproducing the recorded signals by means of a twin head

and for amplifying, limiting and demodulating the recorded signals and

reconverting the third signal into its original frequency range and

combining the so reconverted third signal and said first signal.

d of recording and reproduction of wide frequency band video

signals onto or from a magnetizable recording carrier, carried out by

the following means: means for separating of the video frequency signals

into first and second signals of lower and upper frequency range

respectively, for converting said second signal into a third signal the

frequency range of which equaling that of said first signal, for

frequency modulating a carrier wave frequency by said first and third

signals and for recording the frequency modulated signals by means of a

twin head, for reproducing the recorded signals by means of a twin head

and for amplifying, limiting and demodulating the recorded signals and

reconverting the third signal into its original frequency range and

combining the so reconverted third signal and said first signal. mprising:

mprising:  ach other. A

carrier frequency located at about 4 MHz is frequency-modulated with the

brightness signal, which is limited to 2.7 MHz. The chrominance signal

is moved out of its original frequency position into a new frequency

range, which is located lower than that of the lower side bands of the

frequency-modulated brightness signals. Thereafter the

frequency-converted color signals are added and recorded.

ach other. A

carrier frequency located at about 4 MHz is frequency-modulated with the

brightness signal, which is limited to 2.7 MHz. The chrominance signal

is moved out of its original frequency position into a new frequency

range, which is located lower than that of the lower side bands of the

frequency-modulated brightness signals. Thereafter the

frequency-converted color signals are added and recorded.  at full utilization of the advantages of frequency

modulation. The color television system (NTSC, PAL or SECAM) does not

influence the recording, so that the same apparatus can be used for all

systems, except of course, for different power supply frequencies.

at full utilization of the advantages of frequency

modulation. The color television system (NTSC, PAL or SECAM) does not

influence the recording, so that the same apparatus can be used for all

systems, except of course, for different power supply frequencies.  e pre-emphasis and the modulation

itself; the last is indicated by a common carrier wave oscillator 16.

The signal, which is frequency modulated in 13, is applied by way of an

amplifier 14 to a further magnetic head 15, which is preferably combined

with the magnetic head 5 to form a twin head, recording simultaneously

with head 5 parallel tracks without any interspace. Technologically, the

amplifiers 4 and 14 and the heads 5 and 15 are of equal design; as

later will be explained, only the azimuth angles of the gaps of heads 5

and 15 differ from each other.

e pre-emphasis and the modulation

itself; the last is indicated by a common carrier wave oscillator 16.

The signal, which is frequency modulated in 13, is applied by way of an

amplifier 14 to a further magnetic head 15, which is preferably combined

with the magnetic head 5 to form a twin head, recording simultaneously

with head 5 parallel tracks without any interspace. Technologically, the

amplifiers 4 and 14 and the heads 5 and 15 are of equal design; as

later will be explained, only the azimuth angles of the gaps of heads 5

and 15 differ from each other.  without having to extract the chrominance signal out

of the color television signal and without having information carried by

the amplitude of the magnetization, which exists at the tape. For this

latter reason, the width of the tracks may be further decreased, and in

this way, the playing time can be again increased.

without having to extract the chrominance signal out

of the color television signal and without having information carried by

the amplitude of the magnetization, which exists at the tape. For this

latter reason, the width of the tracks may be further decreased, and in

this way, the playing time can be again increased.  pe speed of 6000 mm/s and an azimuth-angle of 8° Which

is contrarotating from track to track (which means 16° effective for

each head), and the scanning head deviates by 9% of the track width out

of its track, the cross-talk results in a signal to noise ratio of 20.4

dB. This ratio is too small and must therefore be further diminished by

complicated and expensive electronic means with the help of comb

filters. According to the invention all recorded frequencies are located

at 4 MHz; under otherwise equal circumstances the cross-talk ratio now

amounts to 45 dB, which requires no additional distortion suppressing

means.

pe speed of 6000 mm/s and an azimuth-angle of 8° Which

is contrarotating from track to track (which means 16° effective for

each head), and the scanning head deviates by 9% of the track width out

of its track, the cross-talk results in a signal to noise ratio of 20.4

dB. This ratio is too small and must therefore be further diminished by

complicated and expensive electronic means with the help of comb

filters. According to the invention all recorded frequencies are located

at 4 MHz; under otherwise equal circumstances the cross-talk ratio now

amounts to 45 dB, which requires no additional distortion suppressing

means.  A reversible video cassette for portable video devices is described, said cassette having two housing halves (7, 8), mounted displaceably for changing the distance between the winding spools. The housing halves are connected to each other by two flat guide parts (13, 14) arranged in parallel. The two housing halves are releasably locked by two catch hooks (17, 18) associated with the guide parts.

A reversible video cassette for portable video devices is described, said cassette having two housing halves (7, 8), mounted displaceably for changing the distance between the winding spools. The housing halves are connected to each other by two flat guide parts (13, 14) arranged in parallel. The two housing halves are releasably locked by two catch hooks (17, 18) associated with the guide parts. REIBUNG Die Erfindung betrifft eine

Video-Wendekassette in Form eines im wesentlichen quaderf·ormigen

K·orpers mit zwei darin drehbar gelagerten Wickelspulen f·ur das

Magnetband und einer an einer schmalen L·angsfl·ache vorgesehenen

·Offnung mit teilweise zur·uckgesetzter Geh·ausewand zur freiliegenden

Magnetbandf·uhrung, wobei die Kassette vorzugsweise aus zwei

verriegelbaren im wesentlichen geschlossenen Halbteilen besteht, die zur

Ver·anderung des Wickelspulenabstandes sowie zur Vergr·osserung der

freiliegenden Magnetbandl·ange verschiebbar gelagert sind.

REIBUNG Die Erfindung betrifft eine

Video-Wendekassette in Form eines im wesentlichen quaderf·ormigen

K·orpers mit zwei darin drehbar gelagerten Wickelspulen f·ur das

Magnetband und einer an einer schmalen L·angsfl·ache vorgesehenen

·Offnung mit teilweise zur·uckgesetzter Geh·ausewand zur freiliegenden

Magnetbandf·uhrung, wobei die Kassette vorzugsweise aus zwei

verriegelbaren im wesentlichen geschlossenen Halbteilen besteht, die zur

Ver·anderung des Wickelspulenabstandes sowie zur Vergr·osserung der

freiliegenden Magnetbandl·ange verschiebbar gelagert sind. even numbered to an odd numbered track and for changes

from an odd numbered to an even numbered track.

even numbered to an odd numbered track and for changes

from an odd numbered to an even numbered track.  in oblique parallel tracks cross-talking from track to track

can be kept to a minimum if the tracks are separated by guard bands.

However, such guard bands are a poor way of using the available

recording face.

in oblique parallel tracks cross-talking from track to track

can be kept to a minimum if the tracks are separated by guard bands.

However, such guard bands are a poor way of using the available

recording face.  ng during play-back of video

signals in oblique tracks are known, but were never attractive for

incorporation into devices for home use. For example it has been

suggested to use the time difference which occurs simultaneously with a

migration as a measure of the lateral migration of the replay head from

the magnetic track. This method can be accomplished by very simple

circuitry but poses high demands with respect to the precision and the

timely constancy of such circuits, because very small and continuously

changing time intervals must be measured.

ng during play-back of video

signals in oblique tracks are known, but were never attractive for

incorporation into devices for home use. For example it has been

suggested to use the time difference which occurs simultaneously with a

migration as a measure of the lateral migration of the replay head from

the magnetic track. This method can be accomplished by very simple

circuitry but poses high demands with respect to the precision and the

timely constancy of such circuits, because very small and continuously

changing time intervals must be measured.  ment in magnetic

helical-scan video recording with the aid of rotating magnetic video

heads which are adjustable by a servosystem perpendicularly to the

direction of movement, the servosystem being controlled by a control

signal (burst) of a particular frequency keyed in each case at the

beginning of the track and the area of reproduction of a new track being

located immediately adjacent to the area of recording of the preceding

track, characterized in that the order of recording and reproduction for

the control signal (burst) keyed in arbitrary length, relative to the

scanning movement of the magnetic video head, takes place alternatingly

from track to track and, relative to the beginning of the track, offset

in time and geometry from track to track.

ment in magnetic

helical-scan video recording with the aid of rotating magnetic video

heads which are adjustable by a servosystem perpendicularly to the

direction of movement, the servosystem being controlled by a control

signal (burst) of a particular frequency keyed in each case at the

beginning of the track and the area of reproduction of a new track being

located immediately adjacent to the area of recording of the preceding

track, characterized in that the order of recording and reproduction for

the control signal (burst) keyed in arbitrary length, relative to the

scanning movement of the magnetic video head, takes place alternatingly

from track to track and, relative to the beginning of the track, offset

in time and geometry from track to track. 1. Verfahren zur dynamischen ·aquidistanten

Spureinstellung bei der magnetischen Schr·agspur-Videoaufzeichnung mit

Hilfe von rotierenden Video-Magnetk·opfen, die senkrecht zur

Bewegungsrichtung durch ein Servosystem verstellbar sind, wobei die

Ansteuerung des Servosystems durch ein jeweils am Spuranfang

eingetastetes Steuersignal (Burst) bestimmter Frequenz erfolgt, d a d u r

c h g e k e n n z e i c h n e t dass die Reihenfolge der Aufzeichnung

und Wiedergabe f·ur das in beliebiger L·ange eingetastete Steuersignal

(Burst) bezogen auf die Abtastbewegung des Video Magnetkopfes von Spur

zu Spur alternierend und bezogen auf den Spuranfang von Spur zu Spur

zeitlich und geometrisch versetzt erfolgt, derart, dass der

Wiedergabebereich einer neuen Spur dem Aufzeichnungsbereich der

vorangegangenen Spur unmittelbar benachbart ist.

1. Verfahren zur dynamischen ·aquidistanten

Spureinstellung bei der magnetischen Schr·agspur-Videoaufzeichnung mit

Hilfe von rotierenden Video-Magnetk·opfen, die senkrecht zur

Bewegungsrichtung durch ein Servosystem verstellbar sind, wobei die

Ansteuerung des Servosystems durch ein jeweils am Spuranfang

eingetastetes Steuersignal (Burst) bestimmter Frequenz erfolgt, d a d u r

c h g e k e n n z e i c h n e t dass die Reihenfolge der Aufzeichnung

und Wiedergabe f·ur das in beliebiger L·ange eingetastete Steuersignal

(Burst) bezogen auf die Abtastbewegung des Video Magnetkopfes von Spur

zu Spur alternierend und bezogen auf den Spuranfang von Spur zu Spur

zeitlich und geometrisch versetzt erfolgt, derart, dass der

Wiedergabebereich einer neuen Spur dem Aufzeichnungsbereich der

vorangegangenen Spur unmittelbar benachbart ist.  Die Anwendung des Verfahrens

setzt voraus, dass die aufzeichnenden bzw. wiedergebenden rotierenden

Video Magnetk·opfe senkrecht zu ihrer Abtastrichtung gesteuert bewegbar

sind. Die gesteuerte Bewegbarkeit, wie sie z.B. beim System ~Video 2000"

angewendet wird, dient prim·ar der Spurfindung bei der Wiedergabe.

Hierzu werden zus·atzlich zum Luminanz- und Chrominanzsignal

beispielsweise vier Hilfsfrequenzen aufgezeichnet, die unterhalb des

Chrominanzsignals und Luminanzsignals liegen und die bei der Wiedergabe

in einer Servoschaltung derart verarbeitet werden, dass der

Wiedergabekopf immer so eingestellt wird, dass er auf der gewunschten

Magnetspur l·auft.

Die Anwendung des Verfahrens

setzt voraus, dass die aufzeichnenden bzw. wiedergebenden rotierenden

Video Magnetk·opfe senkrecht zu ihrer Abtastrichtung gesteuert bewegbar

sind. Die gesteuerte Bewegbarkeit, wie sie z.B. beim System ~Video 2000"

angewendet wird, dient prim·ar der Spurfindung bei der Wiedergabe.

Hierzu werden zus·atzlich zum Luminanz- und Chrominanzsignal

beispielsweise vier Hilfsfrequenzen aufgezeichnet, die unterhalb des

Chrominanzsignals und Luminanzsignals liegen und die bei der Wiedergabe

in einer Servoschaltung derart verarbeitet werden, dass der

Wiedergabekopf immer so eingestellt wird, dass er auf der gewunschten

Magnetspur l·auft. mgeschaltet und tastet das

Burstsignal der vorhergehenden Spur ab. Die Amplitude des dabei

gewonnenen Signals ist ein Mass f·ur den Spurabstand und kann zur

Einstellung des rotierenden Magnetkopfes am Spuranfang benutzt werden,

derart, dass die Spurabst·ande konstant sind.

mgeschaltet und tastet das

Burstsignal der vorhergehenden Spur ab. Die Amplitude des dabei

gewonnenen Signals ist ein Mass f·ur den Spurabstand und kann zur

Einstellung des rotierenden Magnetkopfes am Spuranfang benutzt werden,

derart, dass die Spurabst·ande konstant sind. d erreichen.

d erreichen. ·uber der Aufzeichnung um die

Burstl·ange zuz·uglich des doppelten Spurversatzes verschoben ist.

Durch Vertauschung der Reihenfolge von Schreiben und Lesen sowie durch

Einf·ugen einer L·ucke zwischen Schreiben und Lesen in jeder zweiten

Spur um die Dauer des doppelten Spurversatzes wird also sichergestellt,

dass bei verl·angerter Burstdauer das Burstsignal in voller L·ange

gelesen werden kann und trotzdem der Schreib- und Lesevorgang am

Spuranfang verbleibt, wie es f·ur die wirkungsvolle und st·orsichere

Regelung des Spurabstandes n·otig ist.

·uber der Aufzeichnung um die

Burstl·ange zuz·uglich des doppelten Spurversatzes verschoben ist.

Durch Vertauschung der Reihenfolge von Schreiben und Lesen sowie durch

Einf·ugen einer L·ucke zwischen Schreiben und Lesen in jeder zweiten

Spur um die Dauer des doppelten Spurversatzes wird also sichergestellt,

dass bei verl·angerter Burstdauer das Burstsignal in voller L·ange

gelesen werden kann und trotzdem der Schreib- und Lesevorgang am

Spuranfang verbleibt, wie es f·ur die wirkungsvolle und st·orsichere

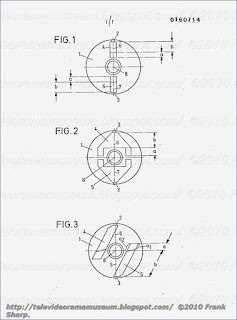

Regelung des Spurabstandes n·otig ist. ayback machine with at least two signal recording and

playback heads (5, 6), which are preferably arranged offset by 180

degrees on a rotating head wheel (2) in a head drum, the transformers

each having one rotating (10', 11') toroidal part and one fixed (10",

11") toroidal part, each signal head (5, 6) being assigned the rotating

part of a transformer in a certain way, and the transformers (10, 11)

being arranged axially one above the other, characterized in that the

transformers (10, 11) have different ring sizes such that they do not

radially overlap.

ayback machine with at least two signal recording and

playback heads (5, 6), which are preferably arranged offset by 180

degrees on a rotating head wheel (2) in a head drum, the transformers

each having one rotating (10', 11') toroidal part and one fixed (10",

11") toroidal part, each signal head (5, 6) being assigned the rotating

part of a transformer in a certain way, and the transformers (10, 11)

being arranged axially one above the other, characterized in that the

transformers (10, 11) have different ring sizes such that they do not

radially overlap. ROTIERENDEN RINGF·ORMIGEN TRANSFORMATOREN IN

EINEM VIDEOGERAT BESCHREIBUNG Die Erfindung betrifft eine Anordnung von

rotierenden ringf·ormigen Transformatoren zur induktiven Ubertragung

hochfrequenter Schwingungen in einem Video-Aufzeichnungs- und

Wiedergabeger·at mit wenigstens zwei Signal-Aufzeichnungs- und

Wiedergabek·opfen, die vorzugsweise um 1800 versetzt auf einem

rotierenden Kopfrad in einer Kopftrommel angeordnet sind, und jedem

Signalkopf der rotierende Teil eines Transformators in bestimmter Weise

zugeordnet ist.

ROTIERENDEN RINGF·ORMIGEN TRANSFORMATOREN IN

EINEM VIDEOGERAT BESCHREIBUNG Die Erfindung betrifft eine Anordnung von

rotierenden ringf·ormigen Transformatoren zur induktiven Ubertragung

hochfrequenter Schwingungen in einem Video-Aufzeichnungs- und

Wiedergabeger·at mit wenigstens zwei Signal-Aufzeichnungs- und

Wiedergabek·opfen, die vorzugsweise um 1800 versetzt auf einem

rotierenden Kopfrad in einer Kopftrommel angeordnet sind, und jedem

Signalkopf der rotierende Teil eines Transformators in bestimmter Weise

zugeordnet ist. 0' mit der geringeren Ringgr·osse befindet sich

hingegen auf der inneren Planseite 14 des Kopfrades. Die H·ohe des

Flansches entspricht bei dieser Anordnung wenigstens der gesamten

Querschnittsh·ohe eines kompletten Transformators.

0' mit der geringeren Ringgr·osse befindet sich

hingegen auf der inneren Planseite 14 des Kopfrades. Die H·ohe des

Flansches entspricht bei dieser Anordnung wenigstens der gesamten

Querschnittsh·ohe eines kompletten Transformators. A system is provided for extending the playing time of standardized

V2000 video cassettes. The system utilizes a rotating head drum having mounted

thereon a first set of video heads displaced 180° with respect to each

other, a second set of video heads displaced by a certain amount from

180° with respect to each other, a rotating winding of a transformer,

and relays to interconnect the heads of either the first or second set

of heads with the rotating winding as the head drum rotates. The relays

are controlled by stationary coils and logic to respond to the setting

of switches to enable the system to operate at normal tape speed via the

first set of heads or reduced tape speed via the second set of heads

without requiring any change in the speed of rotation of the head drum.

A system is provided for extending the playing time of standardized

V2000 video cassettes. The system utilizes a rotating head drum having mounted

thereon a first set of video heads displaced 180° with respect to each

other, a second set of video heads displaced by a certain amount from

180° with respect to each other, a rotating winding of a transformer,

and relays to interconnect the heads of either the first or second set

of heads with the rotating winding as the head drum rotates. The relays

are controlled by stationary coils and logic to respond to the setting

of switches to enable the system to operate at normal tape speed via the

first set of heads or reduced tape speed via the second set of heads

without requiring any change in the speed of rotation of the head drum. sport, a tape transport drive, a rotating head

drum, means for rotating said head drum, a first pair of video heads

mounted on said head drum and displaced from each other by 180°, and a

transformer having a rotating winding mounted to said head drum and a

stationary winding; the improvement comprising: a second pair of video

heads mounted to said head drum and displaced from each other by an

angle slightly different from 180° and control means to interconnect

said first pair of video heads and said rotating winding when said tape

transport drive is operated at a normal speed and to interconnect at

least one of the video heads of said second pair and said rotating

winding when said tape transport drive is operated at a lower, extended

play speed.

sport, a tape transport drive, a rotating head

drum, means for rotating said head drum, a first pair of video heads

mounted on said head drum and displaced from each other by 180°, and a

transformer having a rotating winding mounted to said head drum and a

stationary winding; the improvement comprising: a second pair of video

heads mounted to said head drum and displaced from each other by an

angle slightly different from 180° and control means to interconnect

said first pair of video heads and said rotating winding when said tape

transport drive is operated at a normal speed and to interconnect at

least one of the video heads of said second pair and said rotating

winding when said tape transport drive is operated at a lower, extended

play speed.  id

second pair of video heads comprises a record/playback head and a

playback only head; said switch means further has a "record" position and a "playback" position and further comprising

id

second pair of video heads comprises a record/playback head and a

playback only head; said switch means further has a "record" position and a "playback" position and further comprising  t of said tachometer generator by a second fixed integer

to reduce it to the frame frequency when said tape transport operates

at a lower speed;

t of said tachometer generator by a second fixed integer

to reduce it to the frame frequency when said tape transport operates

at a lower speed;  ds to said rotating transformer winding; said first and said

second polarized relays being displaced from each other by 180° and

being actuated in both positions by first and second stationary coils

excited through logic circuits under the control of position pulses of

said head drum and of the switching mode of operative switches, said

operative switches being shiftable between normal or long play or record

or playback positions.

ds to said rotating transformer winding; said first and said

second polarized relays being displaced from each other by 180° and

being actuated in both positions by first and second stationary coils

excited through logic circuits under the control of position pulses of

said head drum and of the switching mode of operative switches, said

operative switches being shiftable between normal or long play or record

or playback positions.  with

claim 7 further comprising a tachometer generator and a frequency

divider for the output pulses of said tachometer generator; said

tachometer generator being secured to and producing a plurality of

pulses per revolution of said tape transport drive; the frequency of

said tachometer generator output pulses being an integral multiple of

the frame frequency of the video signal at both the rated normal and the

rated low speed of said tape transport drive; and said frequency

divider being switchable between two division factors so as to divide to

frame frequency the frequency of said tachometer generator output

pulses at both, the rated normal and the rated low speed of said tape

transport drive.

with

claim 7 further comprising a tachometer generator and a frequency

divider for the output pulses of said tachometer generator; said

tachometer generator being secured to and producing a plurality of

pulses per revolution of said tape transport drive; the frequency of

said tachometer generator output pulses being an integral multiple of

the frame frequency of the video signal at both the rated normal and the

rated low speed of said tape transport drive; and said frequency

divider being switchable between two division factors so as to divide to

frame frequency the frequency of said tachometer generator output

pulses at both, the rated normal and the rated low speed of said tape

transport drive.  system for extending the playing time of standardized video cassettes in

which each of two rotating video heads, displaced relative to each

other by 180°, records or scans one slant track per television field.

system for extending the playing time of standardized video cassettes in

which each of two rotating video heads, displaced relative to each

other by 180°, records or scans one slant track per television field.  system, this multiple was chosen as

11.

system, this multiple was chosen as

11.

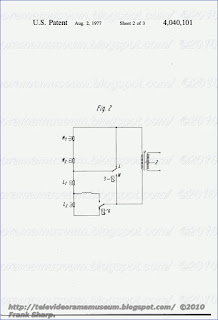

6 is

also provided to connect both heads L1 and L2 to the transformer winding during L mode-playback but only head L1 to the transformer winding during L mode-record. The electrical contacts of the polarized relays 3 and 6 are shown in FIG. 2.

6 is

also provided to connect both heads L1 and L2 to the transformer winding during L mode-playback but only head L1 to the transformer winding during L mode-record. The electrical contacts of the polarized relays 3 and 6 are shown in FIG. 2.  In

addition to the above, gates 7 and 9 each have another input connected

to a position pickup 13. Pickup 13 comprises a simple transducer

designed to generate a pulse each time a small permanent magnet 14 which

rotates with the head drum rotates past the pickup. Thus, the polarized

relay 3 is activated through coils 4 or 5 each time the magnet 14 moves

past the position pickup and is therefore controlled by either the

gates 7 or 9 depending on whether switch 11 is in the "L" or "N"

position.

In

addition to the above, gates 7 and 9 each have another input connected

to a position pickup 13. Pickup 13 comprises a simple transducer

designed to generate a pulse each time a small permanent magnet 14 which

rotates with the head drum rotates past the pickup. Thus, the polarized

relay 3 is activated through coils 4 or 5 each time the magnet 14 moves

past the position pickup and is therefore controlled by either the

gates 7 or 9 depending on whether switch 11 is in the "L" or "N"

position.  When the

tape drive is started (and switch 11 is thus in the L mode -- playback,

tape start position) the relay 3 is switched to the L position via AND

gate 19, OR gate 16 and AND gate 9. In addition 20 ms later relay 6 is

energized to the playback position via AND gate 10 so that the two heads

L1 and L2 are connected in series with the transformer coil 2.

When the

tape drive is started (and switch 11 is thus in the L mode -- playback,

tape start position) the relay 3 is switched to the L position via AND

gate 19, OR gate 16 and AND gate 9. In addition 20 ms later relay 6 is

energized to the playback position via AND gate 10 so that the two heads

L1 and L2 are connected in series with the transformer coil 2.  In

both the N and L modes of operation the start of each slant track has

to coincide with the start of a field and hence phase control of the

head drum 2 is required. This is accomplished by means of a phase

comparator 20 which compares pulses from the pickup 13 with reference

pulses from an outside reference source 21. The reference pulses could,

for example, comprise the vertical synchronous pulses separated from the

video signal. The output of the comparator 21 is fed to an amplifier 22

which feeds the drive motor 23 of the head drum 1.

In

both the N and L modes of operation the start of each slant track has

to coincide with the start of a field and hence phase control of the

head drum 2 is required. This is accomplished by means of a phase

comparator 20 which compares pulses from the pickup 13 with reference

pulses from an outside reference source 21. The reference pulses could,

for example, comprise the vertical synchronous pulses separated from the

video signal. The output of the comparator 21 is fed to an amplifier 22

which feeds the drive motor 23 of the head drum 1.  Usually,

during recording, the servo control of the tape transport motor compares

the frequency and phase of the actual values of a tachometer generator

coupled with the transport shaft with reference values which generally

are derived from the frame frequency and which are simultaneously

recorded on the magnetic tape as a separate synchronization track. Here

the control accuracy of the tape transport becomes greater, the larger

the number of pulses which are delivered by the tachometer generator per

revolution of the transport shaft. The previously mentioned conditions

for the mutual spacing of the slant tracks recorded on the tape and the

dependence of this spacing on line duration also applies analogously to

L-operation. However, since in L-operation only every other field is

recorded the track spacing, as measured in the lengthwise direction of

t

Usually,

during recording, the servo control of the tape transport motor compares

the frequency and phase of the actual values of a tachometer generator

coupled with the transport shaft with reference values which generally

are derived from the frame frequency and which are simultaneously

recorded on the magnetic tape as a separate synchronization track. Here

the control accuracy of the tape transport becomes greater, the larger

the number of pulses which are delivered by the tachometer generator per

revolution of the transport shaft. The previously mentioned conditions

for the mutual spacing of the slant tracks recorded on the tape and the

dependence of this spacing on line duration also applies analogously to

L-operation. However, since in L-operation only every other field is

recorded the track spacing, as measured in the lengthwise direction of

t he tape, must now correspond to an odd multiple of whole lines. The

result is that the transport velocity of the magnetic tape in

L-operation must not be exactly equal to one-half of that in

N-operation, but may be somewhat greater or smaller.

he tape, must now correspond to an odd multiple of whole lines. The

result is that the transport velocity of the magnetic tape in

L-operation must not be exactly equal to one-half of that in

N-operation, but may be somewhat greater or smaller.  rror signal produced in 32 controls the

motor 26 via the control amplifier 41.

rror signal produced in 32 controls the

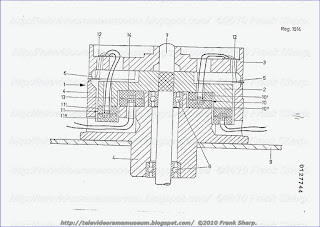

motor 26 via the control amplifier 41.  s

which define an annular gap for magnetic heads which orbit in a chamber

between the drums and engage inclined tracks at the inner side of the

helix. The heads are mounted on a disk which is rotatable on a sleeve

surrounding with clearance a shaft for the drums and having an internal

protuberance which is tiltable with respect to the periphery of the

shaft by a rod extending through an opening in the flange of one of the

drums. The inclination of the plane of orbital movement of the heads

relative to the central symmetry plane of the gap is changed when the

speed of lengthwise movement of tape during playback deviates from the

speed of lengthwise movement of tape during recording.

s

which define an annular gap for magnetic heads which orbit in a chamber

between the drums and engage inclined tracks at the inner side of the

helix. The heads are mounted on a disk which is rotatable on a sleeve

surrounding with clearance a shaft for the drums and having an internal

protuberance which is tiltable with respect to the periphery of the

shaft by a rod extending through an opening in the flange of one of the

drums. The inclination of the plane of orbital movement of the heads

relative to the central symmetry plane of the gap is changed when the

speed of lengthwise movement of tape during playback deviates from the

speed of lengthwise movement of tape during recording. d on or reproduced from magnetic tape which is moved lengthwise

and forms a helix about the peripheral surfaces to two coaxial drums

which surround a shaft, wherein the peripheral surfaces of said drums

define an annular gap for at least one magnetic head which orbits in a

first plane and thereby engages inclined tracks of said helix, and

wherein said gap has a central symmetry plane which is normal to the

common axis of said drums, a combination comprising a carrier for said

head, said carrier being disposed between said drums; means for rotating

said carrier to thereby orbit said head along said gap; and means for

changing the inclination of said first plane relative to said symmetry

plane when the speed of tape movement during reproduction deviates from

the speed of tape movement during recording so as to conform the path of

said head to the inclination of tracks on said helix, comprising a

bearing assembly for said carrier and including a sleeve intermediate

said drums and rotatably supporting said carrier coaxial with the same,

said sleeve having an internal surface space

d on or reproduced from magnetic tape which is moved lengthwise

and forms a helix about the peripheral surfaces to two coaxial drums

which surround a shaft, wherein the peripheral surfaces of said drums

define an annular gap for at least one magnetic head which orbits in a

first plane and thereby engages inclined tracks of said helix, and

wherein said gap has a central symmetry plane which is normal to the

common axis of said drums, a combination comprising a carrier for said

head, said carrier being disposed between said drums; means for rotating

said carrier to thereby orbit said head along said gap; and means for

changing the inclination of said first plane relative to said symmetry

plane when the speed of tape movement during reproduction deviates from

the speed of tape movement during recording so as to conform the path of

said head to the inclination of tracks on said helix, comprising a

bearing assembly for said carrier and including a sleeve intermediate

said drums and rotatably supporting said carrier coaxial with the same,

said sleeve having an internal surface space dly surrounding said shaft

and having a protuberance tiltably engaging the periphery of said shaft,

and tilting means actuatable for tilting said bearing assembly with

respect to the common axis of said drums to thereby change the

inclination of said sleeve.

dly surrounding said shaft

and having a protuberance tiltably engaging the periphery of said shaft,

and tilting means actuatable for tilting said bearing assembly with

respect to the common axis of said drums to thereby change the

inclination of said sleeve.  agnetic tape along

the peripheral surfaces to two coaxial drums which define an annular gap

for one or more magnetic heads mounted in the interior of the drum and

serving to record or reproduce information on the tape. The diameters of

the peripheral surfaces are identical or nearly identical and the

portion of tape which engages such peripheral surfaces forms a helical

loop (e.g., an alpha loop or an omega loop). One of both drums may be

driven or head against rotation about their common axis. The magnetic

head or heads are mounted on a carrier or bracket which relates about

the common axis of and is located between the drums. The plane in which

the carrier rotates the head or heads coincides with the central plane

of the gap between the peripheral surfaces of the drums.

agnetic tape along

the peripheral surfaces to two coaxial drums which define an annular gap

for one or more magnetic heads mounted in the interior of the drum and

serving to record or reproduce information on the tape. The diameters of

the peripheral surfaces are identical or nearly identical and the

portion of tape which engages such peripheral surfaces forms a helical

loop (e.g., an alpha loop or an omega loop). One of both drums may be

driven or head against rotation about their common axis. The magnetic

head or heads are mounted on a carrier or bracket which relates about

the common axis of and is located between the drums. The plane in which

the carrier rotates the head or heads coincides with the central plane

of the gap between the peripheral surfaces of the drums.  f the invention is to provide s

single mechanical device which maintains the magnetic heads of a

helical scan apparatus in accurate register with the track even if the

speed of magnetic tape during reproduction varies and deviates from the

speed during recording.

f the invention is to provide s

single mechanical device which maintains the magnetic heads of a

helical scan apparatus in accurate register with the track even if the

speed of magnetic tape during reproduction varies and deviates from the

speed during recording.  mbly preferably comprises a sleeve which is disposed

intermediate the drums and rotatably supports the carrier. The sleeve

has an internal surface which spacedly surrounds the shaft and has a

preferably annular protuberance (e.g., a spherical or prismatic bearing)

which tiltably engages the periphery of the shaft. The tilting means is

actuatable to change the inclination of the sleeve which is coaxial

with the carrier so that the inclination of the first plane with respect

to the symmetry plane changes in response to tilting of the sleeve. The

protuberance is preferably located in or immediately adjacent to the

symmetry plane. The sleeve is held against axial movement relative to

the shaft.

mbly preferably comprises a sleeve which is disposed

intermediate the drums and rotatably supports the carrier. The sleeve

has an internal surface which spacedly surrounds the shaft and has a

preferably annular protuberance (e.g., a spherical or prismatic bearing)

which tiltably engages the periphery of the shaft. The tilting means is

actuatable to change the inclination of the sleeve which is coaxial

with the carrier so that the inclination of the first plane with respect

to the symmetry plane changes in response to tilting of the sleeve. The

protuberance is preferably located in or immediately adjacent to the

symmetry plane. The sleeve is held against axial movement relative to

the shaft.  a rotor 8

mounted on the carrier 5 and a stator 9 mounted in the drum 1'. The

means for rotating the carrier 5 includes a drive having a motor 19

(FIG. 2) an endless belt or cord 10 engaging a sheave-like portion of

the hub 5a.

a rotor 8

mounted on the carrier 5 and a stator 9 mounted in the drum 1'. The

means for rotating the carrier 5 includes a drive having a motor 19

(FIG. 2) an endless belt or cord 10 engaging a sheave-like portion of

the hub 5a.  The internal surface of the bearing sleeve 7 has an

annular bearing portion or protuberance 11 which engages with the

peripheral surface of the shaft 2 in or very close to the central

symmetry plane X--X of the gap 3. The aforementioned clearance between

the internal surface of the bearing sleeve 7 and the peripheral surface

of the shaft 2 has a first portion at one side and a second portion at

the other side of the bearing portion 11. The upper end of the bearing

sleeve 7 (as viewed in the drawing) has a larger-diameter portion or

collar 13 which is connected with a pin- or rod-shaped tilting member 12

extending with clearance through an opening ID' in the flange 1B' of

the drum 1'. If the member 12 is pushed or pulled in the direction

indicated by arrow A or B, or moved axially, the sleeve 7 is tilted with

respect to the shaft 2 and thereby chang

The internal surface of the bearing sleeve 7 has an

annular bearing portion or protuberance 11 which engages with the

peripheral surface of the shaft 2 in or very close to the central

symmetry plane X--X of the gap 3. The aforementioned clearance between

the internal surface of the bearing sleeve 7 and the peripheral surface

of the shaft 2 has a first portion at one side and a second portion at

the other side of the bearing portion 11. The upper end of the bearing

sleeve 7 (as viewed in the drawing) has a larger-diameter portion or

collar 13 which is connected with a pin- or rod-shaped tilting member 12

extending with clearance through an opening ID' in the flange 1B' of

the drum 1'. If the member 12 is pushed or pulled in the direction

indicated by arrow A or B, or moved axially, the sleeve 7 is tilted with

respect to the shaft 2 and thereby chang es the inclination of the plane

of orbital movement of heads 4 with respect to the symmetry plane X--X

of the gap 3. Thus, by moving the member 12, one can move the

tape-contacting portion of the head 4 above or below the central plane

of the gap 3. This enables the head 4 to conform to the changed position

of scan lines on video tape 20 which is being moved along the gap 3,

with or relative to the peripheral surface 1A and/or 1A'. The position

tracks on the tape with respect to the head 4 changes if the speed of

tape, during reproduction of information, deviates from the speed during

recording. A package of dished springs 14 is interposed between the

flange 1B' and the collar 13 to bear against the collar and to bias the

sleeve 7 to a desired neutral position while permitting for tilting of

the sleeve in response to shifting of the member 12. The carrier 5

shares the tilting movements of sleeve 7 under the action of the member

12. In FIG. 1, the plane of orbital movement of the heads 4 coincides

with the symmetry plane X--X.

es the inclination of the plane

of orbital movement of heads 4 with respect to the symmetry plane X--X

of the gap 3. Thus, by moving the member 12, one can move the

tape-contacting portion of the head 4 above or below the central plane

of the gap 3. This enables the head 4 to conform to the changed position

of scan lines on video tape 20 which is being moved along the gap 3,

with or relative to the peripheral surface 1A and/or 1A'. The position

tracks on the tape with respect to the head 4 changes if the speed of

tape, during reproduction of information, deviates from the speed during

recording. A package of dished springs 14 is interposed between the

flange 1B' and the collar 13 to bear against the collar and to bias the

sleeve 7 to a desired neutral position while permitting for tilting of

the sleeve in response to shifting of the member 12. The carrier 5

shares the tilting movements of sleeve 7 under the action of the member

12. In FIG. 1, the plane of orbital movement of the heads 4 coincides

with the symmetry plane X--X.  NG VON

ROTIERENDEN MAGNETK·OPFEN PATENTANSPR·UCHE

NG VON

ROTIERENDEN MAGNETK·OPFEN PATENTANSPR·UCHE n die Piezoelemente schr·ag (a1,

a2) in die rotierende Halterung eingespannt sind.

n die Piezoelemente schr·ag (a1,

a2) in die rotierende Halterung eingespannt sind.  net. An ihren anderen Enden

sind die Piezoelemente in einen Piezoelementhalter 1 eingespannt, der

entweder selbst als rotierendes Teil ausgebildet oder mit dem

rotierenden Kopfrad des Videorecorders starr verbunden ist. Die

Einspannl·ange der Piezoelemente in die Piezoelementhalter ist mit a

bezeichnet.

net. An ihren anderen Enden

sind die Piezoelemente in einen Piezoelementhalter 1 eingespannt, der

entweder selbst als rotierendes Teil ausgebildet oder mit dem

rotierenden Kopfrad des Videorecorders starr verbunden ist. Die

Einspannl·ange der Piezoelemente in die Piezoelementhalter ist mit a

bezeichnet. l·ost, dass die Piezoelemente schr·ag zur Verbindungslinie

zwischen zugeordnetem Magnetkopf und Drehpunkt der rotierenden Halterung

bis etwa in die H·ohe dieses Drehpunktes verlaufen und dass die

Piezoelemente zur Vermeidung von Azimutfehlern schr·ag in die rotierende

Halterung eingespannt sind.

l·ost, dass die Piezoelemente schr·ag zur Verbindungslinie

zwischen zugeordnetem Magnetkopf und Drehpunkt der rotierenden Halterung

bis etwa in die H·ohe dieses Drehpunktes verlaufen und dass die

Piezoelemente zur Vermeidung von Azimutfehlern schr·ag in die rotierende

Halterung eingespannt sind. Durch

die Anordnung der Piezoelemente 4, 5 schr·ag zur Verbindungslinie 6, 7

zwischen zugeordnetem Magnetkopf 2, 3 und Drehpunkt 8 der rotierenden

Halterung 1 bis etwa in H·ohe dieses Drehpunktes wird die

freischwingende L·ange jedes Piezoelementes vergr·ossert. An ihren

anderen Enden sind die Piezoelemente in den Piezoelementhalter 1

eingespannt.

Durch

die Anordnung der Piezoelemente 4, 5 schr·ag zur Verbindungslinie 6, 7

zwischen zugeordnetem Magnetkopf 2, 3 und Drehpunkt 8 der rotierenden

Halterung 1 bis etwa in H·ohe dieses Drehpunktes wird die

freischwingende L·ange jedes Piezoelementes vergr·ossert. An ihren

anderen Enden sind die Piezoelemente in den Piezoelementhalter 1

eingespannt. ead on the intended track

is applied to the piezoelectric element of a head which is in tape

contact at that time, and in which arrangement a decaying alternating

voltage for eliminating hysteresis effects of the piezoelectric element

is applied ot the piezoelectric element of a head which is not in tape

contact at that time, characterized by the following features : the

decaying alternating voltage is rectangular and the frequency of the

decaying alternating voltage for eliminating hysteresis effets of the

piezoelectric element is just below the frequency of mechanical

renonance of the piezoelectric element.

ead on the intended track

is applied to the piezoelectric element of a head which is in tape

contact at that time, and in which arrangement a decaying alternating

voltage for eliminating hysteresis effects of the piezoelectric element

is applied ot the piezoelectric element of a head which is not in tape

contact at that time, characterized by the following features : the

decaying alternating voltage is rectangular and the frequency of the

decaying alternating voltage for eliminating hysteresis effets of the

piezoelectric element is just below the frequency of mechanical

renonance of the piezoelectric element. r

abklingenden Wechselspannung zur Beseitigung von Hystereseeffekten des

Piezoelemen tes liegt knapp unterhalb der mechanischen Reso nanzfrequenz

des Piezoelementes.

r

abklingenden Wechselspannung zur Beseitigung von Hystereseeffekten des

Piezoelemen tes liegt knapp unterhalb der mechanischen Reso nanzfrequenz

des Piezoelementes.  bei die Magnetk·opfe an Piezoelementen befestigt sind und

jeder Kopf w·ahrend einer Vollumdrehung des Kopfrades eine

Bandeingriffphase und eine Nichteingriffphase hat, und wobei an das

Piezoelement eines Kopfes, der gerade imBandeingriff steht, eine

Spannung angelegt wird, die den Kopf auf der vorgesehenen Spur h·alt,

und wobei an das Piezoelement eines Kopfes, der gerade nicht im

Bandeingriff steht, eine abklingende Wechselspannung zur Beseitigung des

Hystereseeffektes des Piezoelementes angelegt wird.

bei die Magnetk·opfe an Piezoelementen befestigt sind und

jeder Kopf w·ahrend einer Vollumdrehung des Kopfrades eine

Bandeingriffphase und eine Nichteingriffphase hat, und wobei an das

Piezoelement eines Kopfes, der gerade imBandeingriff steht, eine

Spannung angelegt wird, die den Kopf auf der vorgesehenen Spur h·alt,

und wobei an das Piezoelement eines Kopfes, der gerade nicht im

Bandeingriff steht, eine abklingende Wechselspannung zur Beseitigung des

Hystereseeffektes des Piezoelementes angelegt wird. der ein auf einem Piezoelement befestigter Magnetkopf

w·ahrend der Bandeingriffsphase durch das Anlegen einer positiven oder

negativen Gleichspannung an eine vorgegebene Stelle gebracht wird. Nach

dem Abschalten dieser Gleichspannung am Beginn der Nichteingriffsphase

kehrt die Kopf-Piezoelement-Einheit nicht wieder exakt in ihre

Ausgangsposition zur·uck, da aufgrund des Hystereseeffektes im

Piezoelement eine Restauslenkung verbleibt, die die Nullpunktlage der

Kopf-Piezoelement-Einheit ver·andert. Demzufolge werden bei der

n·achsten Bandeingriffsphase dieses Kopfes Spurfehler auftreten.

der ein auf einem Piezoelement befestigter Magnetkopf

w·ahrend der Bandeingriffsphase durch das Anlegen einer positiven oder

negativen Gleichspannung an eine vorgegebene Stelle gebracht wird. Nach

dem Abschalten dieser Gleichspannung am Beginn der Nichteingriffsphase

kehrt die Kopf-Piezoelement-Einheit nicht wieder exakt in ihre

Ausgangsposition zur·uck, da aufgrund des Hystereseeffektes im

Piezoelement eine Restauslenkung verbleibt, die die Nullpunktlage der

Kopf-Piezoelement-Einheit ver·andert. Demzufolge werden bei der

n·achsten Bandeingriffsphase dieses Kopfes Spurfehler auftreten. ten Bandeingriffsphase wird dem Piezoelement w·ahrend der

Nichteingriffsphase eine abklingende sinusf·ormige Wechselspannung

zugef·uhrt, die die fehlerhafte Nullpunktlage der Kopf

Piezoelement-Einheit beseitigt, d. h. die Restauslenkung des Kopfes